Stock Market’s Wild Mood Swings Can Be Explained by Mr. Spock

Think of the “Star Trek” character and the calm punctuated by fits of euphoria and bouts of despair will be easier to understand.

Bloomberg, June 22, 2020

Clients, colleagues and even family members keep asking the same question: “Why have stocks decoupled from the economy?” These are not people who obsess over the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet or spend time with the Bureau of Labor Statistic’s birth-death model. They just want to know what’s going on in the stock market.

Recently, the gulf between peoples’ daily experiences and the market has never been greater. It is a huge source of confusion. Traders are alternately exuberant and panicked, swinging markets up or down 10% in a day. In March, indexes fell 34% from record highs just a month earlier; despite horrific news about the economic blow from the coronavirus shutdowns, stocks then jumped 44% from those lows. My Bloomberg Opinion colleague John Authers describes it as the “insanity trade.”

No wonder the public thinks Mr. Market is bipolar. The average person doesn’t want to hear abstract academic arguments that markets are probabilistic mechanisms, collectively allocating capital by incorporating imperfect information about an inherently unknowable future. These explanation are clearly unsatisfying.

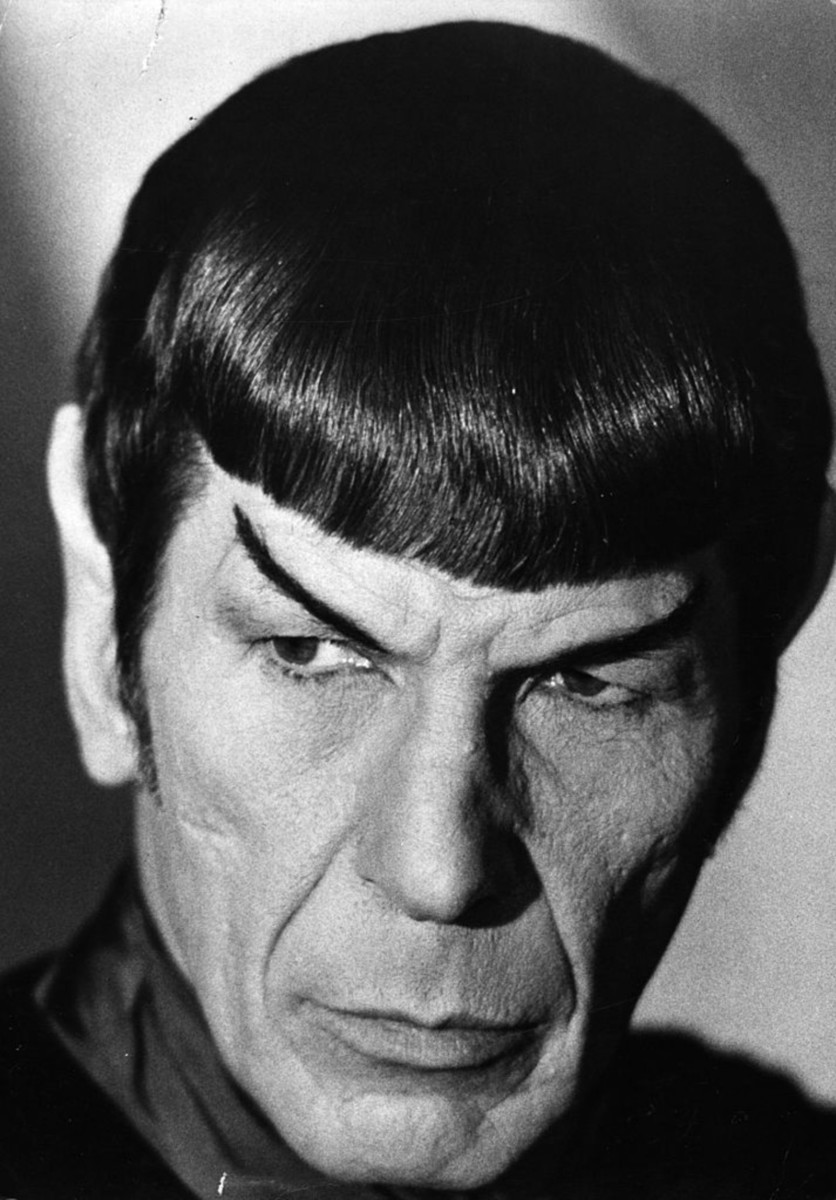

But maybe there is a simple explanation. In short, one shouldn’t think about the “stock market.” Instead, think of it as the “Spock market.” 1

A short explanation for those who are not familiar with the “Star Trek” TV and film franchise: Mr. Spock is the science officer and second in command aboard the starship U.S.S. Enterprise; his mother was human while his father was a Vulcan, a race that only managed to save itself from violence and war by turning to hyper-rationalism. Spock’s human half, of course, is emotional and irrational and his logical side struggles to keep it under control.

Once you think of Mr. Market as Mr. Spock, the raging disconnect between the economy and equity prices becomes easier to grasp. Consider the following points:

Investors are rational: Much of the time, markets are understandable and make intuitive sense to investors. When the economy is expanding and profits are rising, so do stocks. If the economy tanks, shares plunge. There are long periods when stocks meander higher, reflecting positive developments in technology, taxes and inflation. This is the Vulcan logic of equities, reflecting investors’ rational, quantitative calculations of value.

Investors are irrational: Sometimes, markets seem to bounce from giddiness to panic almost overnight. It is especially obvious at turning points: Recall the March 2000 dot-com highs, when new companies were trading at 100 times earnings. Or the March 2009 financial-crisis lows, when prices were cut in half and selling was indiscriminate. The points where groupthink takes over the crowd, where emotions run rampant and greed and fear can overwhelm investors — that’s the human half at work. The Nobel prize committee recognized these two opposite forces in 2013. 2

Most recently, we’ve seen this with day traders buying bankrupt companies because their prices are rising while others sell quality holdings at very low prices because others have also done so. Irrational investors create opportunities for those few who recognize this.

Markets are efficient: The volume of information is so enormous, it can never be fully grasped by one person. Yet prices reflect all of what is known, which gets communicated to all participants through the impact of buying and selling.

Price, in other words, is the most efficient collective probability bet about the future. Very rational, indeed.

Markets are very inefficient: Efficient, yes, except when those efficient expressions turn out to be wildly wrong. Note this is not when a trade turns out to be a money-loser. Rather, it’s when the analytical framework underlying the trade turns out to be completely unfounded.

This is where our emotional half sends the rational half off the rails. Rather than describing markets as efficient, it is more accurate to describe markets as efficient except when they’re not.

Most investors do not know they don’t know: Most explanations of recent market behavior reflect hindsight bias detailing what everyone now knows. It is rare to hear someone asked a question about a market move and not give a detailed after-the-fact explanation. Few are willing to admit that they really don’t know or that many market moves are simply random.

Here, Mr. Spock is quite different. He often notes his lack of understanding with a simple response of “fascinating.” His logic and ego control allow the admission of not knowing. He is subject to the Dunning-Kruger effect much less than most. Investors often get into trouble when they imagine they have an understanding about things they don’t.

Spock’s mixed human-Vulcan heritage was a great plot device that allowed “Star Trek” to subtly comment on the human condition, exploring the tension between logic and emotion, between our intellectual capacities and our baser drives.

Investors who recognize and take account of the Spock market will better understand what is going on, and — one can hope — use it to guide their actions for better results.

_____________

1. Not to be confused with the trading game of the same name — Spock Market — was similar to fantasy football, only with Star Trek characters during reruns and a sort of drunken bingo: “The Spock Market is actually kind of fun. You set up an account and are given 15,000 Federation Credits or FDR. You can then buy and sell different “stocks” based on characters and items from the show. For instance, my portfolio is composed of Scotty (SCT), Chekov (CKV), Communicator and Communications, Inc (COM), Federation Costume and Uniform (FCU), Dilithium Mining and Mineral (DMI) and Red Shirt (RDS). The object is to be one of the top 6 Traders.”

2. By awarding the Nobel Prize to both Eugene Fama and Robert Shiller, the committee acknowledged this schism. Fama’s thesis was that the pricing mechanism of markets were so efficient that they were difficult (if not impossible) to beat; Shiller’s data overwhelmingly showed that markets could be as irrational as the humans who traded in them. Bubbles form, prices detach from reality, then crash.

~~~

I originally published this at Bloomberg, June 22, 2020. All of my Bloomberg columns can be found here and here.