Is the Stock Market Overvalued, Cheap or Just Right? A Debate

Valuation metrics can help in investment decisions, but they’re also subject to misuse and misinterpretation.

Bloomberg, July 9, 2020

Most discussions about the stock market eventually get around to the question of valuation: Are shares prices too high, too low or just right? But valuation may not offer the answers investors want to hear. Bloomberg Opinion columnists Nir Kaissar and Barry Ritholtz recently met online to debate.

Barry: Value as a measure means much less than many people imagine.

That sounds controversial, but it shouldn’t be. “Stocks are pricey, overvalued and prone to crash” is something I have been hearing since the early 1990s.

Valuation measures are not useless; they just are not the be-all metric many believe. Valuation provides a rough range of expected returns – but only a broad estimate. In reality, fair value is a level that markets tend to careen past on their way to becoming incredibly cheap or wildly expensive. It is not a point where equities ever spend much time.

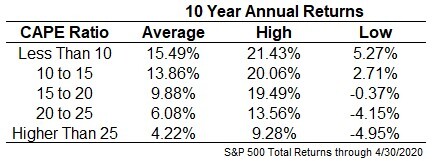

As the table below shows, averages can be misleading. The cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings ratio, or CAPE, produces a broad range of possible outcomes. Sometimes low CAPEs yield mediocre returns; other times expensive CAPEs generate very good returns.

Source: Ben Carlson

Here is a radical statement: For much of the past three decades valuation measures haven’t been a useful guide for buying or selling equities.

Valuations matter — just not as much as many people believe.

Nir: I would argue that valuations matter more than people realize. If used properly, valuation is among the most powerful tools available to investors.

Here’s why: Most financial decisions require an estimate of future returns from investments. The problem, of course, is that no one can predict the future. So the question is, What is the most reliable way to estimate future returns.

This is where valuation comes in handy. There’s a strong correlation, for instance, between the U.S. stock market’s valuation, as measured by earnings yield (the inverse of the famed price-to-earnings ratio), and subsequent returns. That is, high earnings yields have historically signaled higher future returns and vice versa. From 1881 to June 2010, the longest period for which numbers are available, the correlation between the S&P 500 Index’s earnings yield and its subsequent 10-year total real return was 0.56, counted monthly. That’s based on cyclically adjusted earnings, but the correlation is similar using other measures of earnings.

~~~

I originally published this at Bloomberg, July 9, 2020. All of my Bloomberg columns can be found here and here.