One of Economic’s great mysteries has long been the lack of measurable productivity growth in America. Whenever we look at this issue, three likely possibilities seem to fall into one of categories:

1. Its a measurement issue;

2. Productivity varies so greatly from sector to sector, our personal views are skewed;

3. The real economy is actually failing to become more productive;

My starting point was we can’t find productivity gains due to our outdated methodology of measuring productivity — a legacy from earlier industrial era. And of course, the 3rd options is a non-starter. However, I will admit to recognizing my own bias as a white collar worker in various services industries — finance, publishing, radio/podcasting — has altered my perspective due to the massive productivity gains in those sectors.

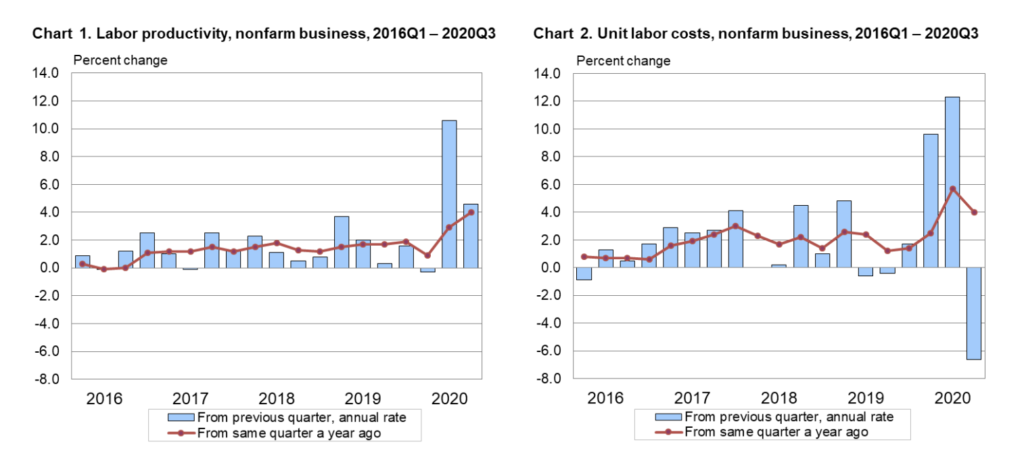

Which makes the past few months of outsized productivity gains even more fascinating fodder for discussion. Consider the details from the latest Bureau of Labor Statistics release* on Productivity:

-Nonfarm labor productivity increased 4.6% in Q3 2020

-Output increased 43.4%

-Hours worked increased 37.1%

-Nonfarm labor productivity increased 10.6% in Q2 2020

-Unit labor costs decreased at an annual rate of 6.6% in Q3 2020 (hourly compensation fell 2.3%;

-Trailing 4 quarters productivity increased 4.o%, reflecting a 3.4%-decline in output and a 7.1% decline in hours worked.

One of the accidental results of the pandemic lockdown was the creation of a natural experiment in productivity ( calculated by dividing an index of real output by an index of hours worked by all persons).

Consider: Those who could work from home using technology like computers/broadband did so. These are primarily services industry workers who might have previously had lots of personal contacts — from sales to therapists — but could adapt to current circumstances via software like Zoom, Slack, Hangout, Facetime, etc. These same people no longer had to commute to the office, or do lots of little time killing errands related to work. Instead, they were practically on call 24/7, and able to work continuously during lockdown. They are the top right arm of the K, and their productivity levels likely went up quite significantly.

The sectors that were hit hardest by lockdown include those who work face to face: Think retail, food service, hospitality, travel, healthcare etc. So many people in these sectors lost their jobs; even with the recovery many are still unemployed. These seem to be the people in the bottom right arm of the K, These the sectors have proven very resistant to productivity gains.

Note: It is hard to know for sure given the massive spike in unemployment and the subsequent massive (yet still incomplete) recovery. But it makes the sector thesis of missing productivity that much more likely.

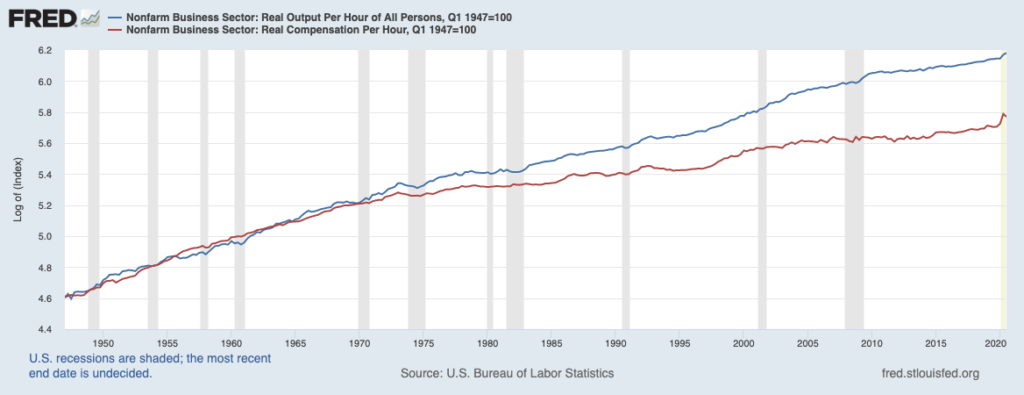

This chart below raises this question of a corollary to the impact of divergent productivity by sector on long-term increasing income (and wealth) inequality. Asked differently, is widening inequality a function of differing sector-by-sector productivity gains? Are the white collar professional tech enabled jobs leaving the services industry far behind?

Productivity Gains: Output versus Compensation

Source: FRED Hat tip Invictus

Previously:

The K-Shaped Recovery (September 4, 2020)

Productivity Puzzle Becomes More Complicated (November 2, 2016)

Why Can’t We Find Productivity Gains? (April 4, 2016)

See also:

The compensation-productivity gap: a visual essay

Susan Fleck, John Glaser, and Shawn Sprague

Monthly Labor Review • January 2011

________

* All quarterly percent changes in this release are seasonally adjusted annual rate.

Source: Image by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay