Philippa Dunne is one of the editors of The Liscio Report, an independent research newsletter focusing on the U.S. labor market, debt issues, and international flows. Their work includes month-by-month tracking of tax revenues at the state level, and detailed analysis of federal data releases.

~~~

TLRWire: What’s cheaper than a new line of fighter jets?

In his wonderful When the Earth Had Two Moons, planetary geologist Erik Asphaug points out after bearing “the brunt of earth’s gravity for another three years in storage,” when the Galileo mission was finally launched, 2 ribs of the umbrella-like antennae that was to beam data back down failed to open. That forced the back-up antennae, capable of transmitting less than 0.1% of the high-gain antenna’s capacity, to takeover. Enter image compression, now known as the JPEG, and 70% of the data mission was accomplished. Whew.

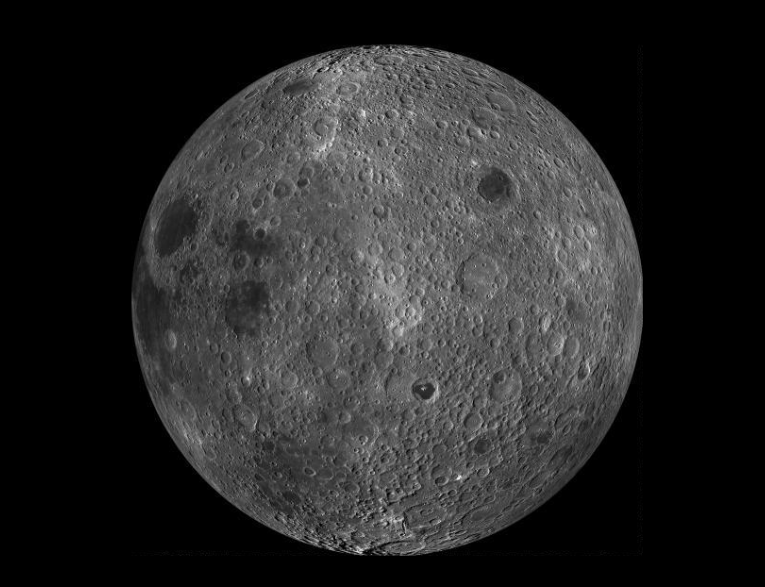

But sharing his many stories—that Columbus knew the size of the earth, it had been established for centuries, but intentionally underbid the cost & complexity to make it happen; how, in the 3rd century BC, Archimedes invented exponential notation to show that grains of sand are countable only in principle, “but that does not make them infinite. Is that distinction philosophical, or is it crucial?”; that asteroids have to be “soft and yielding,” in order to escape catastrophic destruction, the survival of the weakest; that Martian meteorites in museums would fill a wheelbarrow (although there are likely billions of tons scattered around the world); or that there were once two moons in our sky—are not what drove Asphaug to write his book.

He wrote his book because as we are pushing deeper into deep space exploration, we are also “pushing the limits of our planet…. Staring into Hubble’s Deep Field…feeling sparse and alone, painted into a corner…And yet we’re lost.” This is a very tough scientist writing.

To break out of our “shell, stars painted on the canopy,” we need more planetary exploration. His solution, published in 2019, is to double our space exploration budget, probe for nearby planetary systems and Near Earth Objects, and “start soon so we might get there by our great-grandkids’ lifetimes.”

He then outlines his “practical solutions to global problems.” Highlighting our history of forming colonies to compete for “combative status,” aided by technology such as better catapults, he calls war a visionless industry, but that the same means of production can be repurposed. Think Apollo, “a muscular display of super-power derring-do.”

Writing before the pandemic, he calls the ecological crisis “a nudge,” to move from “using every tool to gain dominion,” to the “fundamentally mammalian qualities” of “nurturing our offspring and living in alliance.” He outlines how all nations have cooperated in our space efforts, including our providing data to China for her first manned mission.

He calls it “lucky news” that one day another asteroid will bring devastation to our earth, and that we might consider that “the stick,” with “asteroid resources” being the carrot, to get the ball rolling.

This is not a new idea. Carnegie’s Alan Dressler, who nurtured my interest in these things decades ago and went on to work in the team that provided evidence for the black hole at the center of our galaxy (don’t get scared when it suddenly brightens!) wrote in his Voyage to the Great Attractor back in 1994 that we should find a way to preserve ourselves and our great works elsewhere—of course at that time he was thinking about the sun’s upcoming explosion.

Here’s Asphaug’s ending sentence, “But this whole idea, of once-hazardous asteroids captured as international resource outposts, while Earth is returned to its garden state—these are no more chapters of science fiction than reading a book on a tablet while gazing out an airplane window would have seemed to a cowboy of the 1950s.”

Apollo brought us together as a species, “however briefly.” And was much less expensive than “rolling out a new line of fighter jets or nuclear submarines.”

Philippa

Research by-product: This could be us

From NASA, always free