In the midst of a deep dive into employment data, I happened across some off-the-beaten-path analysis of the Teen Labor market: Why Teenage Workers Are Leading the Recovery.

Conor Sen makes a few fascinating observations here:

“What makes teenage employment useful to study right now is that teenagers are less affected by the factors holding back labor supply than any other demographic. If they lived at home with their parents, they weren’t eligible for economic impact payments. If they were full-time students, they’d be ineligible for unemployment insurance, making enhanced benefits a nonfactor. They’re unlikely to be parents squeezed out of the labor force by closed schools or a lack of child care. They’re obviously not older workers who may have accelerated retirement plans during the pandemic. And teens were less likely to get seriously ill from Covid-19, and so perhaps less likely to avoid working for health-related reasons.”

I have my own theories as to what’s happening in the Labor Pool that goes beyond unemployment and daycare (more on this tomorrow). But there are some intriguing anomalies worth delving into regarding teens.

Start with this: “In May, for the first time in history, the jobless rate for teenagers was lower than the rate for workers aged 20 to 24.” Normally, the unemployment rate for teenagers is ~5% more than the next age bracket.

Another fascinating data point: “The employment-to-population ratio for teenagers hit a 13-year high in May.”

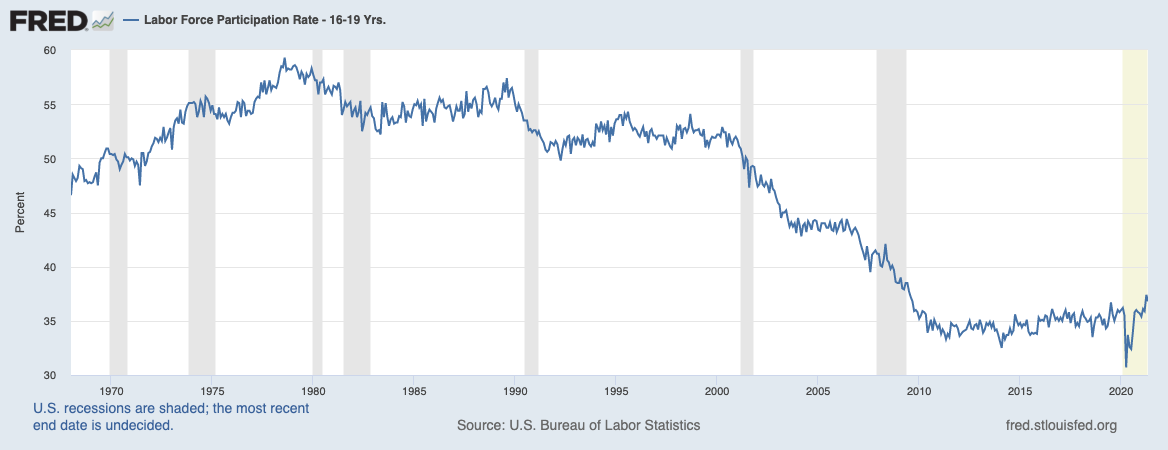

Consider this chart:

Labor Force Participation Rate for 16-19 Yrs

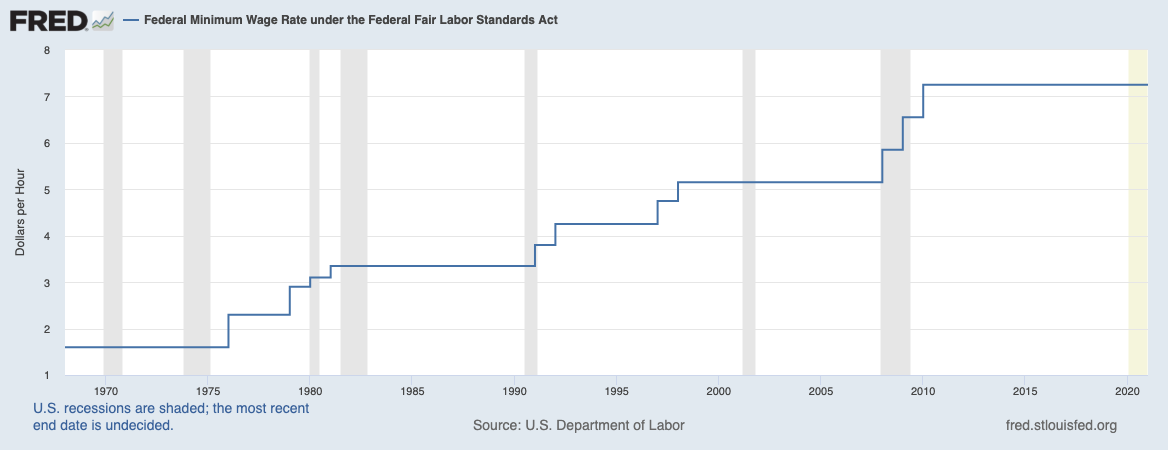

There is a deep socio-economic story written in that. It contains changing motivations and mores for multiple generations. And, I believe combined with the minimum wage chart (top) over the same period, it’s telling quite a compelling narrative.

My pet theory: The lagging minimum wage has kept teens from the workforce.

In 2007, before the great financial crisis, the national minimum wage level was a paltry $5.15. This was not all that long ago. For a teenager with even the most modest withholding / FICA, their take-home is so small it’s not worth it to work. You can see that in the trends over the preceding decades. By most measures — productivity, profitability, inflation, exec comp — the minimum wage has lagged badly. Teens did the math, and said WTF, why bother?

But the minimum wage began to rise during the financial crisis despite skyrocketing unemployment. It was raised in 2008, and then in 2009, and again in 2010. Post GFC, it’s been $7.25 an hour.

Not coincidentally, at exactly that time, the labor participation rate of teenagers began trending upwards. Today, it’s even higher than it was before the pandemic began. Maybe it’s boredom, perhaps some teens just want out of the house where they’ve been stuck with mom and dad and their siblings during the past year.

Or just maybe, local employers are raising wages sufficiently to make summer jobs attractive to teens.

More interesting employment data tomorrow

Source:

Why Teenage Workers Are Leading the Recovery

by Conor Sen

Bloomberg, June 8, 2021

https://bloom.bg/3zdd62J

Previously:

Wages in America

Shifting Balance of Power? (April 16, 2021)