History Shows War Shocks Have a Modest Impact on Equities

Market reactions to dangerous events like Russia’s war in Ukraine tend not to damage stock valuations over the long term.

BusinessWeek, March 2, 2022

After Russia rolled tanks and troops into Ukraine, markets sold off—for half a day. S&P 500 futures tumbled overnight, but by 2:30 p.m. in New York on Feb. 24, the S&P 500 was higher than before military action began. While there’s been volatility, U.S. equities as of March 1 were still up since before the invasion.

A lot of clients at my wealth management firm called and wrote to ask how that could be. The short answer is, this isn’t unusual. Historically, events such as wars, assassinations, and terror attacks are just not that meaningful to the factors that drive markets. These horrific events exact a terrible human toll, as measured in casualties and injuries, human suffering, and refugees. But the immediate reaction to dangerous mass conflicts like the war in Ukraine tends not to affect equity valuations over the long term. What drives equity prices are increased corporate revenue and profit, and the typical geopolitical event isn’t big enough to change those very much. The impact on global gross domestic product is modest in all but a few outlier cases.

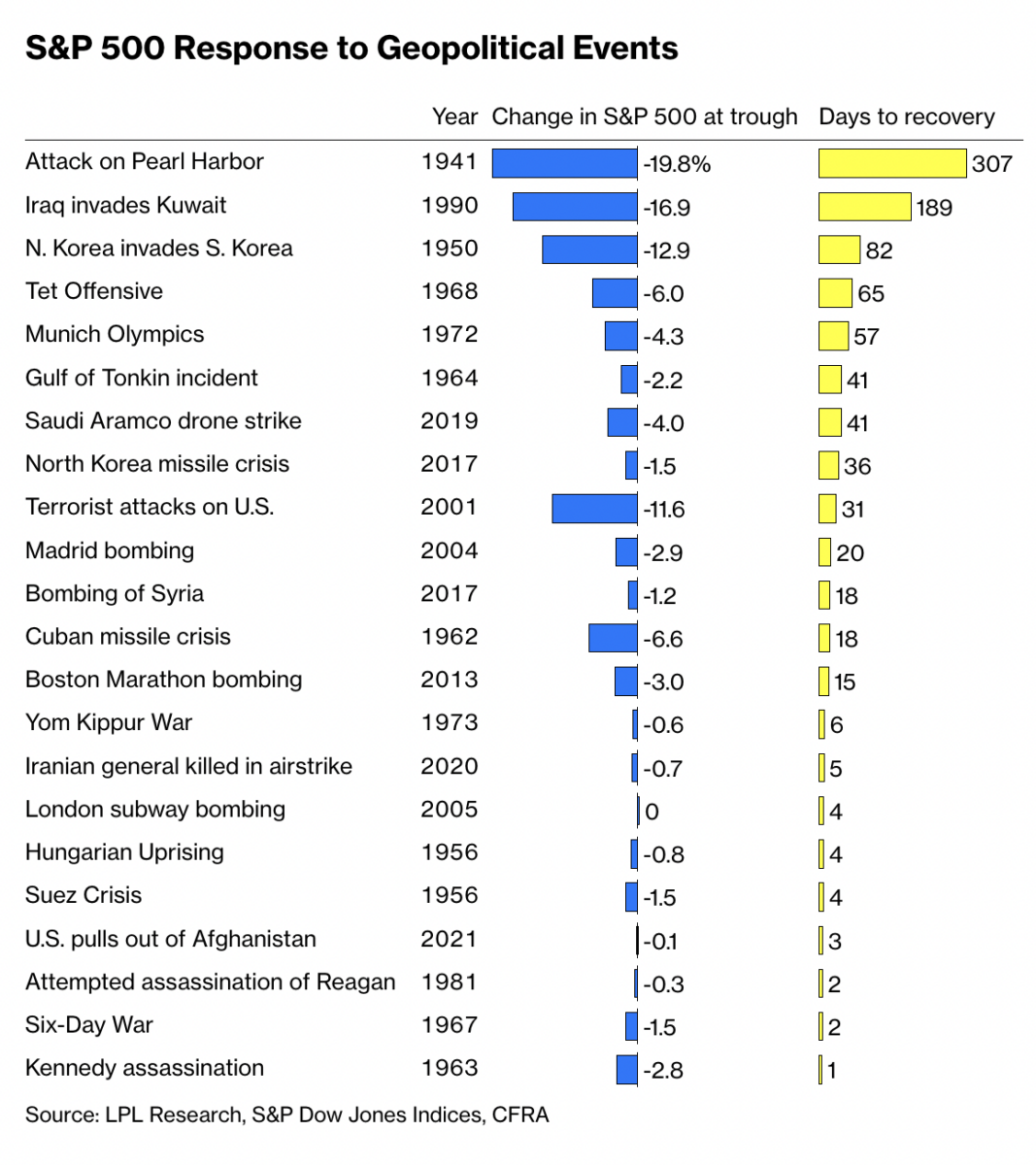

Ryan Detrick, chief market strategist at LPL Financial, looked at 22 major nonfinancial shocks, from the Pearl Harbor attack onward. While no two events were the same, the stock market had a way of shaking them off quickly, he says. These events on average led to a one-day loss of about 1.1%. Total drawdowns from geopolitical events before hitting bottom and climbing back averaged 4.8%. It typically took 19.7 days to complete the drop and 43.2 days to bounce back. Even the U.S. entry into World War II following Pearl Harbor took the market only a year and a half to recover from. The worst war in human history, and U.S. equities needed 143 days to bottom and were higher 307 days later.

There are caveats to this. The U.S. is a geographically isolated superpower, and existential threats to its currency and stock market—short of a nuclear conflagration—are quite low. Wars have very different results in smaller, more vulnerable countries: Looking at Poland in 1939, Afghanistan in 2001, or Russia in 1906, you see that stock, bond, or currency markets suffered greatly. Also, we’ve only seen the beginning of the current conflict. Russia’s GDP, at $1.67 trillion, is relatively small—about the same as Canada’s, which has a quarter of the population. Ukraine’s economy is even smaller. But as the war escalates, it could have an economic impact well beyond those countries’ borders.

Still, the resiliency of markets stands out. The moral is not that you should be complacent about serious events or assume nothing can harm your portfolio, but that you should be cautious about drawing a straight line from the news to turns in the market. Although Wall Street has no shortage of professional commentators on geopolitics, it’s difficult to successfully trade on their forecasts. Markets often stumble on headlines, but soon after these wobbles, they tend to return to whatever the prior trends were.

~~~

Ritholtz is host of Bloomberg’s Masters in Business podcast and chairman and chief investment officer of Ritholtz Wealth Management.