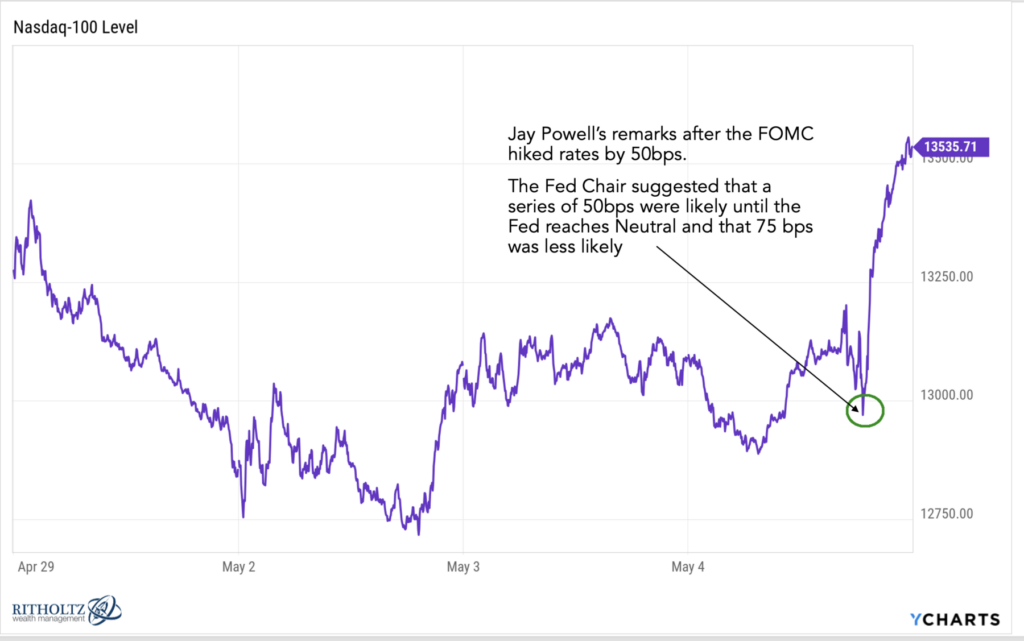

The Force was with markets yesterday: The monster rally was the first ~3% move higher we have seen in quite a while. The S&P 500 gained 2.99%, the beaten-up tech-heavy Nasdaq surged 3.19% and the Russell 2000 tacked on 2.69%.

The move may have come as a surprise to some, but given how oversold and wildly negative traders were, it should not have been. This is not hindsight bias, but simply what I wrote the day before in Too Many Bears: “All this negativity and this spike in bearish sentiment makes me wanna buy equities with both hands.”

But that’s a trading call, not an asset allocation call — I am glad I added the caveat “But alas, prudence requires a more thoughtful approach. Regardless of your desires, any one indicator by itself is rarely sufficient to drive a substantial change in portfolio allocations. There simply are too many moving parts to rely on a single variable.”

Which brings us to the thorny subject of Market Timing, and what makes it so challenging. As noted yesterday:

Market Timing is even harder: There are many reasons why, but perhaps the most compelling is that the biggest up and down days tend to be clustered near each other. Overbought conditions lead to sell-offs aka (lol) profit-taking; oversold conditions lead to snapback rallies, but the long-term trend is where actual capital gets compounded.

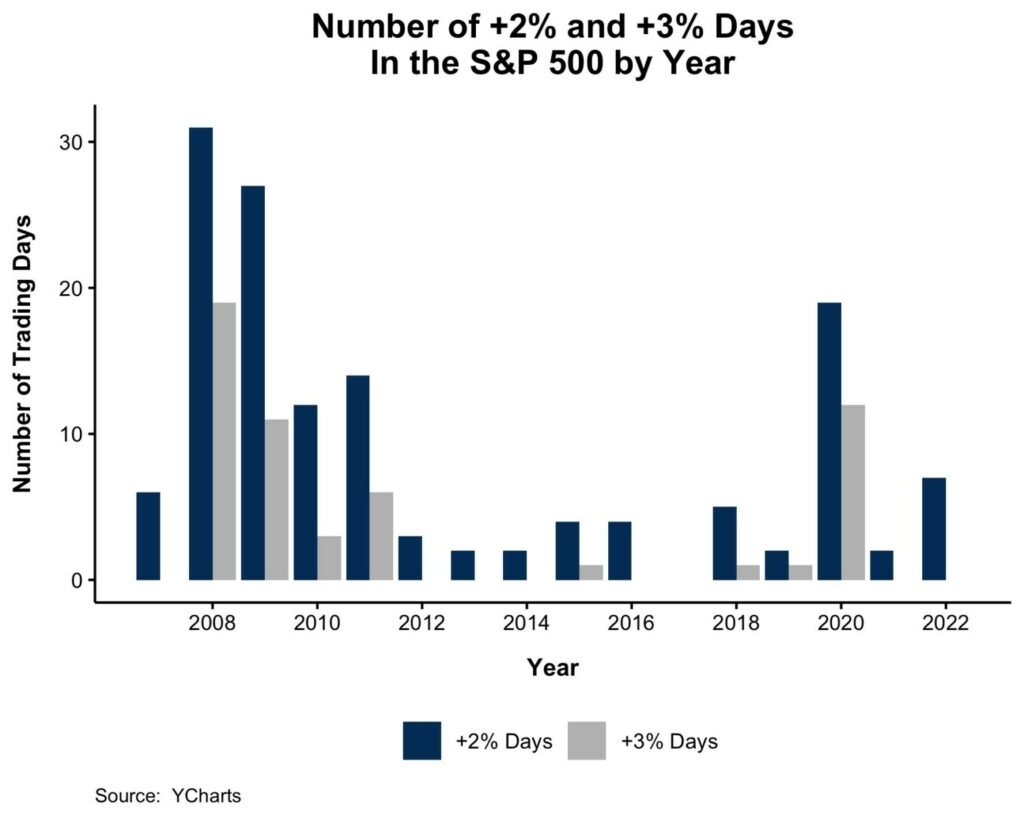

Today is a perfect example of that: Losses today are a mirror image of the gains yesterday. One of the best ways to visualize this phenomenon is in the number of +2% and +3% days. As the chart above shows, the biggest up days tend to all cluster around big down days or during intense bear markets. In 2008, we saw 30 rally days of +2% and almost 20 days of +3% in a year where the S&P500 fell 38.5%. Lotsa of big up days in 2009 too, which saw the market fall another 30% before reversing in March and then rallying to finish the year +23.5%. And similar action was seen in 2020, when a 34% crash led to a year that finished up 16.3%.

I have had about as many good market timing calls in my career as anyone could ever hope for in a finance career, and despite those, I have no interest in slinging around a few billion dollars on my gut instinct. As much as mom insists I am brilliant, how can anyone know how much of these calls are skill and how much is luck?

Short answer: You cannot.

I don’t usually quote musical theater in these missives, but any market timer should go see the 1972 show Pippin, which features this line by Stephen Schwartz:

“A simple rule that every good man knows by heart

It’s smarter to be lucky than it’s lucky to be smart”-War is a Science, Pippin, 1972 (music and lyrics by Stephen Schwartz)

It will be interesting to see what happens next.

See also:

Miss the Worst Days, Miss the Best Days (Batnick, February 8, 2019)

Some Thoughts on Bear Markets (Carlson, March 11, 2022)

This is Where Dragons Lurk (Batnick, May 5, 2022)

Previously:

My Investing Philosophy in a Nutshell (May 4, 2022)

Too Many Bears (May 3, 2022)

Where Sea Monsters Live (May 1, 2012)