@TBPInvictus

Among the more overlooked data sources out there is the Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF). My guess as to why it’s overlooked is that it’s only published triennially – not exactly a high frequency release. The most recent (2013) update was issued last September. As I saw very few, if any, write-ups of that release, I’m guessing I’m not the only observer who overlooked it.

In his always excellent daily (this from July 15, 2015), my pal David Rosenberg did some digging into the SCF, and what he found is quite intriguing, and perhaps goes a long way toward explaining the economy’s seemingly never-ending lethargy and failure to achieve a meaningful “escape velocity.” Let’s have a look.

Dave writes:

“As I ponder the generally soft tone to U.S. retail sales – not just the poor June data and the downward revisions but the lack of follow-through generally in spending, despite stepped-up employment growth, the wealth effect (supposedly) from housing and equity price appreciation, ultra-low interest rates for the past seven years and relief from sharply lower energy prices – I am left with the conclusion that there must be something structural afoot that is keeping just enough households on the sidelines to prevent consumption growth from accelerating.”

“Consumption growth” = demand, which has been, and continues to be, the missing ingredient to a more robust recovery.

Dave notes that household net worth is at a new all-time high (that data from the Fed’s Z.1 Flow of Funds report). And that “the average household has seen its net worth stabilize from 2010 to 2013 (from the SCF) at $534,600.” This much is certainly all true.

He then proceeds to drill down a bit deeper and, in the process, gives a quick lesson on the difference between median and mean.

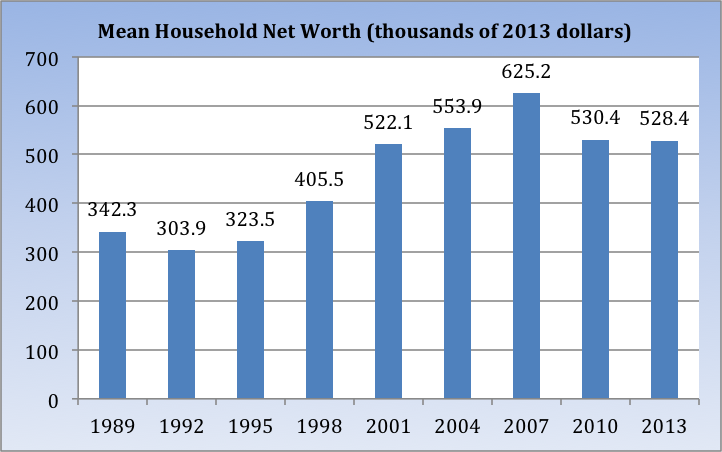

Here’s the mean net worth of all households:

(I note occasional minor discrepancies above and below between Dave’s numbers and mine. We pulled our numbers from slightly different data sets at the same source – Dave from the Fed’s “Internal Data” while I pulled the “Public Data.” The differences are inconsequential.)

Hard to see what all the fuss is about looking at the chart above. Nasty recession. The average household coughed up about 15 percent of its net worth between 2007 and 2010, and things have stabilized since then. No biggy. That notwithstanding the fact that there’s been barely any growth since 2001. But I digress.

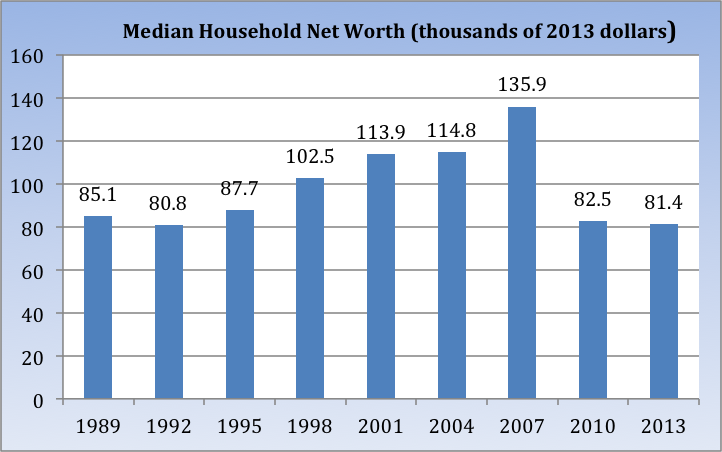

Back to Dave (emphasis mine): “While the average household has seen a 3.7% wage increase (2010 to 2013) to $87,200, the distribution has obviously been very skewed because the median has declined nearly 5% to $46,700, a 20-year low [Ed note: This for the 35-44 age cohort; see below chart]. Indeed, to really show how totals, and how averages can disguise what is really going on behind the scenes, consider that median household net worth in the United States has declined 2% over this time frame to $81,200 and down 24% from the 2007 bubble peak – not just down 24% from 2010 to 2013, but now basically the same level as in 1992.”

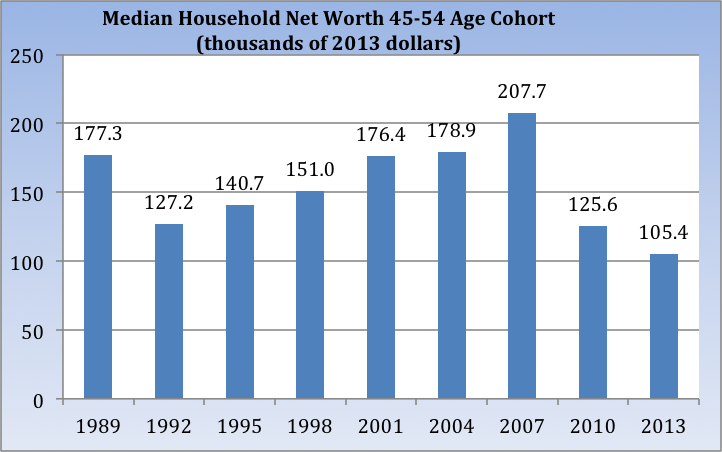

Dave continues: “The bubble-burst destroyed two decades of net worth for the median household. For the 45-54 age cohort (below), median net worth has absolutely plunged – actually declining through the 2010-2013 recovery phase by 17% to $105,300; down 50% from the 2007 peak and some 40% lower today than it was in 1989.”

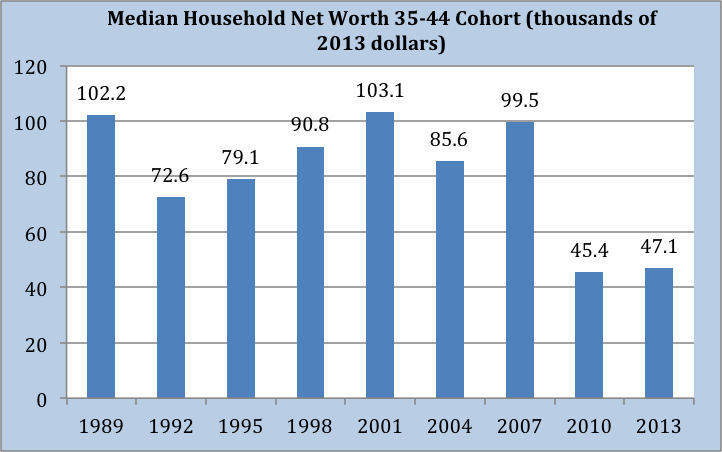

Unsurprisingly, the situation for the 35-44 age cohort is equally dire, only on a lesser scale:

This is all just further evidence of wealth and income inequality and the continued gutting of the middle class. Beyond that, it also speaks to the lack of demand that has been the major culprit behind our stop-and-go recovery. Sadly, it does not look like there’s much light at the end of the tunnel.

This might explain why the savings at the pump appears to be going straight to savings instead of being spent, thereby preventing the growth the economists were predicting. http://www.businessinsider.com/oil-crash-impacts-on-us-consumer-spending-2015-7

Also keep in mid that the 35-44 and 45-54 cohorts are fairly small compared to the main bulges of the baby boomers and millenials. The baby boomers are moving into retirement which means they are going to be very focused on what their net worth is and how much they can afford to spend (probably less than when they were working) while millenials are struggling to get employed and pay off their student debt.

BTW – all of the wailing and rending of garments about the need to cut Social Security and Medicare is not going to create a huge degree of confidence in Baby Boomer consumers. So that political strategy will end up back-firing on the advocates that cutting entitlement programs will create growth.

There is no evidence that trickle-down economics works and lots that it doesn’t but it continues to be the economic mantra of the day.

People fell for the dot com stock bubble. then they fell for the real estate bubble.

“Nobody’s Fault but mine” – Robert Plant – Led Zeppelin.

Considering that house prices have been increasing since 2010 and stocks have gained spectacularly since 2010, I am a little surprised that even the mean “household net worth” is flat for 2010-13. How could those trillions of additional “worth” not have taken the mean higher. As far as I remember the two main components of “worth” are stocks, bonds, and houses. With two of those up substantially how come the total is flat?

This doesn’t change the validity of the points about means/medians and the hurting consumer class.

Stock market is getting smaller because of buybacks. It requires high PEs, low dividend yields etc. to have the high current market value. The market value compared to GDP is similar to 2007, so it has been essentially flat over that period when inflation adjusted. Much of the capital raising for companies is now venture capital and private equity. There haven’t been many new IPOs.

@DeDude: I think part of the difficulty is teasing-out the effects of so many variables impacting mean household net worth. Some of it is housing, some is the price of equities, some is the percent of households holding equities, some is median income, some is unemployment / underemployment, some is the drawdown of savings,/u>… and I’m sure there are other key components as well. Regardelss, a rally in stocks and housing prices may be inadequate to erase the ground lost in the recession years.

@rd: I don’t understand the implied correlation between declines in mean household net worth and the shrinking size of the stock market because of buybacks. I grasp that stock buybacks can artifiicially moderate (or inflate) stock prices, but the correlation between U.S. GDP, productivity and median wages has effectively been broken for decades.

Yes the fall since 2007 is clear and easy to understand. The thing that is puzzling to me is the lack of a rise between 2010 and 2013. Both stocks and house prices went up drastically. But I can see the possible effects from companies purchasing their own stocks. That would be wealth kept in the company and it would not show up on the balance sheets of households.

@bear in mind

The whole stock market cap is what people own, not the actual indices. So if the stock market cap hasn’t gone up significantly in real terms since 2007, then the stock market wealth hasn’t. If the top few percent keep getting a larger chunk of the stock market wealth, then that component for the median household has to drop. The concept of the American Dream is that the pie keeps getting bigger so that everybody gets wealthier – if it stops growing and bigger pieces go to just a few, then the American Dream shrinks for the median folks.

@DeDude Maybe there’s some offsetting factors. The stock market and housing recovery are certainly boosting household wealths at the high end but maybe there’s enough middle income people entering retirement and starting to spend down their wealth or who fell on hard times to offset that.

I’m certainly suspicious too. The wealth distribution is really skewed in this country. Skewed to the point that the bottom half of the country doesn’t matter when talking about average wealth. So I don’t know what could be offsetting the effect of the stock and housing markets. Debt maybe? People borrowing against their newfound home equity again. Even still that would keep their net worth about even rather than cause a loss.

Great presentation of important data points. It is interesting that not many seem to acknowledge what this data says to me which is “economic policy matters” there was a big balance sheet event back in the 80’s as well, remember the RTC? Remember the savings and loan crisis? Also in this data is 911. Looking at this data these events were both less severe and more temporary for all economic classes. At some point we are going need to admit that this is not just demographics and an unforeseeable economic event. There is certainly a component of bad economic policy in the mix. In my view as long as people continue to see “government as the answer” this will create more regulation, more tax burden, and more fear and uncertainty. It seems under the current policies we are doomed to less than 3% GDP growth and so far we have not even seen that.

“In my view as long as people continue to see “government as the answer” this will create more regulation, more tax burden, and more fear and uncertainty.”

Economic policy certainly does matter, quite a bit, so clearly it’s important to accurately state what that policy was.

I’m genuinely curious then why you appear to believe the previous forty years of “government is the problem,” lowered tax burden and less regulation were irrelevant to our current situation or, assuming I’m reading you correctly, may never have happened at all?

RW here is some of the things I see.

#1 The price of housing has gone up substantially as a % of income for the middle class. I believe this is because there is a constrained supply and as new units come on the market they are loaded with soft costs. This constraint is mostly regulation related; there is plenty of land and plenty of people who would like to build inexpensive housing.

#2 One of the things that is missing in this recovery is a blue collar job recovery we should rebuild and build infrastructure in the United States however this is also stifled by over regulation/environmentalism.

#3 The price of education has gone up and the quality has gone down. As BR accurately pointed out universities and the journalist they breed are notoriously liberal. The government has facilitated young people barrowing large amounts of money for a liberal arts education that has no job market. The result is that there are lots of young people saddled with debt, liberal ideas, and no good job prospects.

#4 There is a pervasive movement to tax the rich and redistribute to the poor however in reality we are taxing the middle class and providing incentives for people not to work. There are people who need to work at a place like Wallmart but why work full time when you can work part time and collect government benefits? There is not much acknowledgement that for many it is better to work and gain skills than pay for an overpriced education.

#5 The actual size of people in the government may be level however the cost of these people has gone up exponentially this means that the tax dollars (penalty on work for most) do not bring a virtuous benefit.

#6 Capitalism works however we do not really have a capitalist system today. When the savings and loan crisis hit in the 80’s the institutions were allowed to fail and that created opportunity. In todays world we want the government to save everyone. The big banks, the stock market, the part time workers, the universities. Why bother working hard or making conservative decisions in todays world those ideas are just dumb.

Sure there are other factors like the ability to source cheap labor outside of the united states that may be holding GDP down but there is not much we can do about that if we want to have any chance of competing in the next set of world markets. We could streamline regulations and our tax system and fix our education system before it is to late.

Why do you think we can’t even get to a sustained 3% GDP growth yet?

@4whatistsworth: Interesting list. A couple quibbles I couldn’t quite concur with:

1) “…price of housing has gone up substantially as a % of income for the middle class. I believe this is because there is a constrained supply and … this constraint is mostly regulation related.” Can you cite any data or analysis which supports this supposition? And can you speak to the role of subprime loans and ZIRP apparently NOT having as much of a role in housing prices skyrocketing as “regulation”?

2) “…this is also stifled by over regulation/environmentalism.” Really? Really?! You don’t think the lack of Federal FUNDING by a do-nothing Tea Party-led Congress is as important a factor as regulation(s)? Please educate me on this as I’m not up to speed on these developments.

3) “The price of education has gone up and the quality has gone down.” Hmmm. Price of higher education has certainly increased, but how do you quantify the statement the quality has gone down?

4) This is kind of a hot mess. There’s a reason Frank Luntz separates one talking point from another because they don’t all relate equally to each concept. Most curiously, can you demonstrate where, “There is a pervasive movement to tax the rich…”? because it seems federal statistics prove that the rich are enjoying some of the lowest nominal tax rates than they have in the last century. There’s a Congress in place which will not consider tax increases on the poor put-upon Ritchie Riches of our gilded age, nor will they provide funding for infrastructure, so where’s your evidence of this rabid ‘tax the rich’ movement?

5) “The actual size of people in the government may be level however the cost of these people has gone up exponentially…”. Wow. Do you know what exponentially means? Can you demonstrate, with actual facts and figures, where ‘the cost of these people has gone up exponentially’?

6) Finally, we’re in agreement! The core financial institutions who caused the subprime follies should have been sent to the Resolutiuon Trust Corporation (see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Resolution_Trust_Corporation).

After an orderly winding-down of those organizations, the participants who knowingly defrauded investors, pensions, government agencies, other financial institutions, etc., should have been prosecuted to the fullest extent of the law.

Unfortunately, in the earliest stages of this mess (late-’06 to late-’08) when such an option would have made the most sense, the federal governent was run by the Bush Administration and they wanted no part of prosecuting their Wall Street / fraternity buddies.

Lastly, I cannot begin to fathom how the nefarious actions by Wall Street fat cats are connected to part-time workers and universities. Can you please close that loop for me?

@4whatitsworth, thanks for responding.

“Why do you think we can’t even get to a sustained 3% GDP growth yet?”

Insufficient demand: Our ability to generate sufficient supply is not the problem.

I am not entirely persuaded by the secular stagnation hypothesis but there is enough evidence for it in Europe and possibly elsewhere including here too that I do consider it worth arguing with.

WRT the reasons you see, most appear structural or cultural but those that seem most germane to your argument aren’t large enough in effect IMO:

1. Housing is an important economic driver, true, but other than a few very tight urban markets there is scant evidence of insufficient supply and regardless it is not clear what this has to do with your point: People will rent if they cannot buy but the housing must get built regardless; i.e., the demand for housing exists so prices rise but the means to purchase appears constrained to fewer actors.

2. The essential problem with infrastructure appears to be insufficient funding and the political will to seek revenue for same; regulations and environmental protections appear to be entirely secondary and while they may stall/prevent some projects there is no evidence this is pervasive.

3. Education is certainly important but, once again, I question the relevance to your point: if the kids are educated but cannot find jobs that means insufficient demand for labor and if pay raises haven’t kept up with the times that means the same thing.

4. The rich are not a single category but, yes, most are probably under-taxed because it is relatively easy for them to shield income and the same goes for large corporations; years of effective lobbying have seen to it that a host of avoidance stratagems are available. Assuming wealth or social status is not an excuse to neglect the obligations of citizenship that is an inequity/iniquity that ought to be remedied. On the flipside the total amount a person can earn “on the dole” plus part-time at an employer like Walmart hardly even reaches poverty level: The notion that this is somehow living high-on-the-hog is simply false; urban legend.

5. It is arguable that we have never really had a capitalist system and the notion that there was a golden age of capitalism doesn’t seem strongly grounded in history. I would agree though that things got pretty good post WWII, at least until the 80’s: There were more regulations then and taxes were higher but I wouldn’t argue those were so much causal as symptomatic of a period when demand was strong and a stronger sense of the commons existed too: that decisions made and things built served the country best by serving many rather than a few.