Source: Bankrate

It’s the second-longest bull market in history. Stocks are expensive. This is the top.

At least, that is what I keep hearing — from asset managers, traders and, of course, the news media. I’m not hearing much from the public, which seems to have lost interest in the entire stock-picking/trading/market-timing/macro-event thing, and are focusing instead on making regular contributions to mutual fund indexes viaVanguard and Blackrock.

I want to push back against three ideas:

Length: Those who claim this is the second-longest bull market in history (conveniently) use March 9, 2009, as the starting point. This is incorrect, something I will detail in a future column. The short version is that the bull market really began in 2013, when the major indexes breached the earlier highs set in 2000 and 2007. By that measure, this bull market is only three years old and could easily have a long way to go.

Expensive: It’s easy to draw the conclusion that stocks are pricey. Relative to earnings, they are certainly above their long-term medians. But to reach that conclusion, you must ignore two other important and related factors: Inflation and bond yields, both of which are at or near record lows.

As I have pointed out before (see this and this), you can choose from a variety of measures that show stocks as cheap, expensive and everything in between.

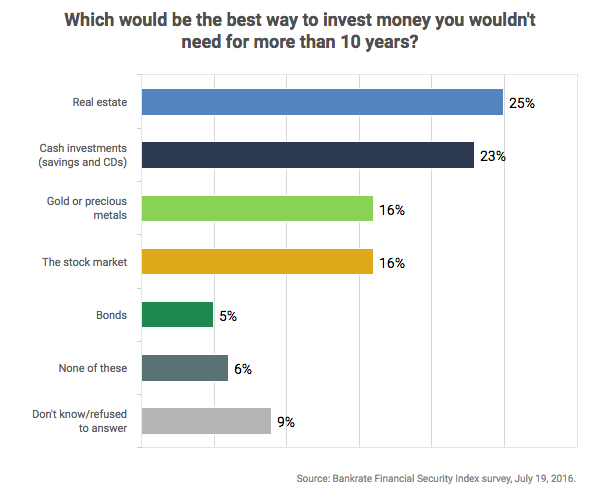

Sentiment: What strikes me the most is the lack of enthusiasm for equities. I was reminded of this by a Bankrate.com poll (see chart below). A quarter of all respondents said the best way to invest money they wouldn’t need to touch for a decade or more was real estate. Next was cash or equivalent investments (23 percent). Stocks came in third, tied with gold and precious metals (16 percent). Back in 2013, four years after the bear market had bottomed, a similar Bankrate.comsurvey found that just 14 percent of Americans believed that stocks were the best long-term investment.

Such a minimal gain in favor of stocks sure doesn’t look like irrational exuberance to me. Bull markets tend not to end when there this little optimism for equities.

There are, of course, a few caveats: This is but one survey, although some others came up with similar findings. And as we have pointed out before, sentiment only matters when it reaches extreme levels of pessimism or optimism. It almost goes without saying, there’s nothing extreme here.

Perhaps there was a touch of hyperbole when, back in October 2009, I called this the “Most Hated Rally in Wall Street History“®. The overall sentiment, despite the strength of the gains after March 2009, was disbelief.

Here’s what I think is going on. Many traders, suffering from the post-traumatic stress of the crash, were unwilling to believe a comeback was even possible. The rally left these frightened folks behind. Blinded by cognitive bias, suffering from recency effects, failing to see both the coming crash and the recovery that followed, many were unable to adapt to or even accept the new market.

I can give you countless reasons why the bull-market rally shouldn’t continue; you can search for the phrase “this stock market will end badly” in Google and find hundreds of thousands of examples. At least so far, that hasn’t been the money-making call.

My favorite thing about capital markets is that each month, each quarter, each year, we learn which argument is correct — at least in terms of the outcome of various risk assets. Unlike in politics, whererepeating false statements over and over can be a winning strategy, markets have a more objective measure of reality: either your analysis makes you money or it does not. It is the ultimate adjudicator.

That negative sentiment would still persist after the stock market has gained so much is an astonishing commitment to — drawing on a somewhat outdated image — fighting the tape.

As Todd Harrison, writing at Minyanville, is so fond of reminding us, the opposite of love isn’t hate; it is indifference.

To me, indifference is long-term bullish.

Originally at This Bull Market Is Powered by Your Indifference