The 95 percent plunge in the shares of Valeant Pharmaceuticals International Inc. since mid-2015 obviously was a disaster for investors who held on for the ride down. Professional traders tend to have risk-management strategies, taking smaller losses to protect capital and avoid a bigger loss. But many investors don’t necessarily have the same tools at their disposal — or the same dispassionate outlook. And so this episode is a teachable moment, and is an important reminder that there are many ways to achieve market-beating returns. Various styles present specific risks, and investors who seek to beat the market should be cognizant of the different hazards these methodologies present.

Most associated with the Valeant debacle is Bill Ackman of Pershing Square Capital Management. His fund’s loss estimates on Valeant range from $2.8 billion to $4 billion. It has to go down as one of the hedge-fund industry’s biggest disasters.

This fiasco is reminiscent of a story recounted by Howard Marks in our recent MIB interview. Marks recalled a chat he had with the head of the pension fund at General Mills Inc. The manager explained to Marks that his fund was “never above the 27th percentile or below the 47th percentile. It was solidly in the second quartile.” The net result of that consistency during a 14 year period was to move the fund into fourth percentile.

This is why Marks says he doesn’t necessarily want to be in the top decile in any given year. The only way to achieve that level of outperformance is to deviate substantially from the relevant index. You must also have be willing to accept the possibility — indeed, probability — that your returns will be in the bottom decile of any given year. As Marks observed, “clients don’t care if I am in top 5 percent, but they don’t want me to be in bottom 5 percent.”

Marks described this in more depth in a Chairman’s Letter back in 1990 called “The Route to Performance“:

“. . . in order to strive for performance which is far different from the norm and better, you must do things which expose you to the possibility of being far different from the norm and worse.

These cases illustrate that bold steps taken in pursuit of great performance can just as easily be wrong as right. Even worse, a combination of far above-average and far below average years can lead to a long-term record which is characterized by volatility and mediocrity.”

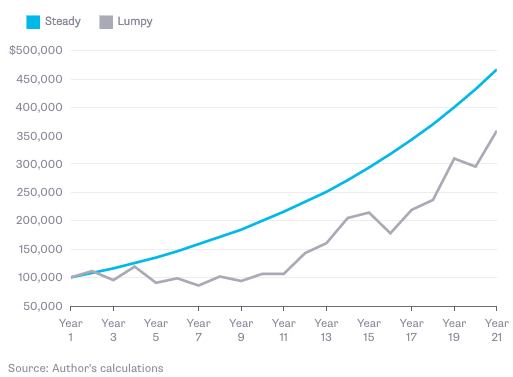

The downside to volatility is that it tends to produce losses that can’t easily be recouped in future years.

To put some flesh on the bones, let’s take two hypothetical managers, both of whom average 8 percent a year for 20 years. Steady gains clearly beat big wins and losses. You can see this in the chart below (see this spreadsheet for more details.)

There is a way for a top-decile manager to beat the consistent second-quartile manager: Have some very big wins, and make sure you have them early in your career to take advantage of the power of compounding returns. The reverse is true as well, and avoiding losses early in your career is crucial.

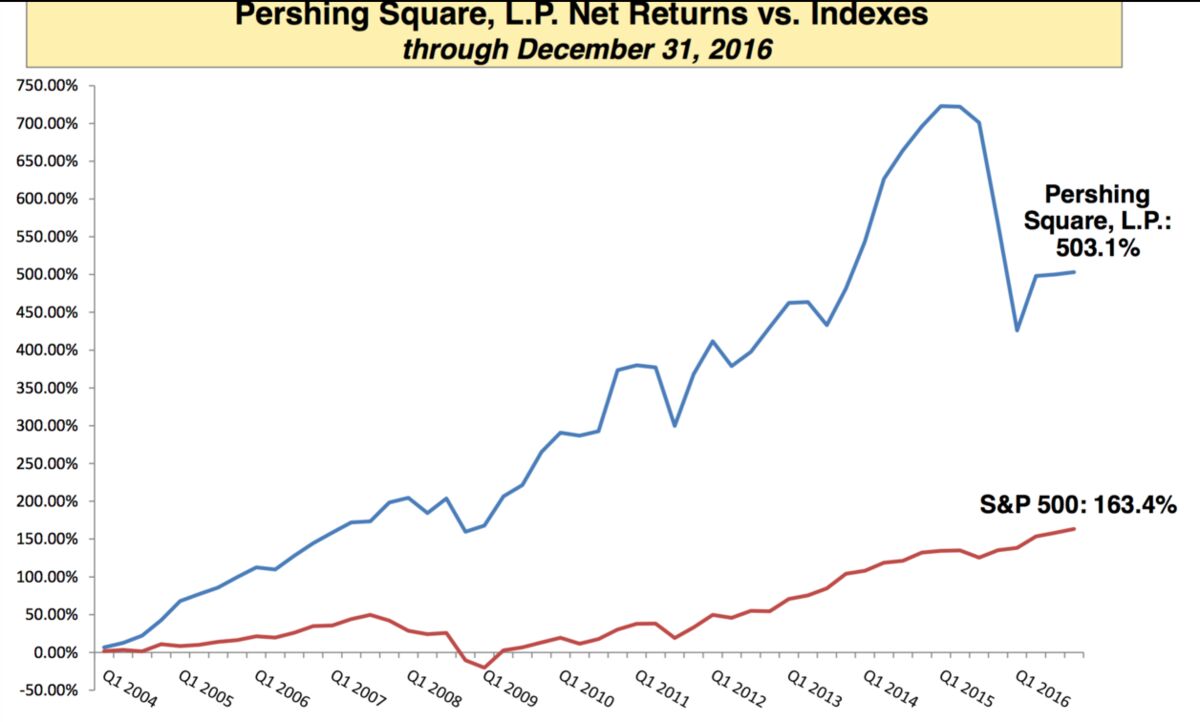

The impact of this can be dramatic. Have a look at this chart produced by Ackman’s Pershing Square. It shows the net returns of the fund from 2004 through Dec. 31, 2016. Even with the big losses from Valeant, shown here with the decline starting in mid-2015, Ackman still trounced the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index by a wide margin. That is an outstanding run, made all the more remarkable by the recent losses.

The lesson for investors is twofold: the first is the importance of being consistent over time. The second is that if you’re aiming for outperformance, make sure you win big early.

Originally: Ackman’s Valeant Bust Shows the Cost of Inconsistency

What's been said:

Discussions found on the web: