The Nasdaq Composite Index, which contains some of the biggest names in tech, hit a milestone this week, crossing 6,000 for the first time. Year-to-date, the Nasdaq has gained almost 12 percent, while the Standard & Poor’s 500 is up 6.6 percent. What this means to future market performance is the subject of ongoing debate: the bulls say new highs presage more gains; the bears see an expensive market beset by risks as the Federal Reserve prepares additional interest-rate increases.

As is so often the case, the truth is both more nuanced and somewhere in the middle.

My context for thinking about markets is the psychology of longer-term secular cycles and how broad or narrow markets are (more on this shortly). Of lesser concern to me are the usual issues of valuation and rising rates. Let’s consider each in turn.

By just about any valuation metric you care to use, U.S. stocks are not cheap; however, too many investors are overly concerned about valuations. Why? Fair value is a theoretical point that stocks careen past on their way to becoming wildly expensive or extremely cheap; it isn’t the point where equities gently come to rest.

Recent history informs us that this matters a great deal to investors. As we have noted before, overvalued stocks can and do stay overvalued for long periods of time. In the mid-1990s, pricey stocks became even pricier, with the S&P 500 notching high double-digit gains for five consecutive years (1995 = 34 percent; 1996 = 20 percent; 1997 = 31 percent; 1998 = 27 percent; and 1999 = 20 percent). If you avoided stocks because they were expensive, you missed a lot of gains. Similarly, in the 1970s, cheap stocks got even cheaper. By the time that decade ended, price-to-earnings ratios were in the single digits — but you had little or nothing to show for buying cheap equities during the prior 15 years; and that’s before accounting for very high inflation.

Thus, valuation alone isn’t the single determining factor many investors believe. Rather, market valuation should help you adjust your future return expectations.

As to those impending rate hikes: Again, history informs us that when rates rise from low levels during periods of modest inflation, stocks tend to do well about three-quarters of the time. More dangerous for equities are those periods of rising interest rates amid high inflation.

Let’s consider the new Nasdaq highs from a longer-term secular perspective. Markets tend to move in long sweeping eras that reflect underlying economic activity; think of the expansions that lasted a decade or two, such as the postwar era (1946-66), or the tech bull market (1982-2000).

As these long booms age, markets tend to simultaneously narrow, and get ahead of themselves. In the 1960s, the “Nifty-Fifty” group of stocks attracted much of the capital, leading to a 1966 peak that wouldn’t be permanently surpassed for 16 years (1982). In the late 1990s, the stampede of the internet powered the Nasdaq to its 2000 peak; it took 15 years for that high to be surpassed (2015).

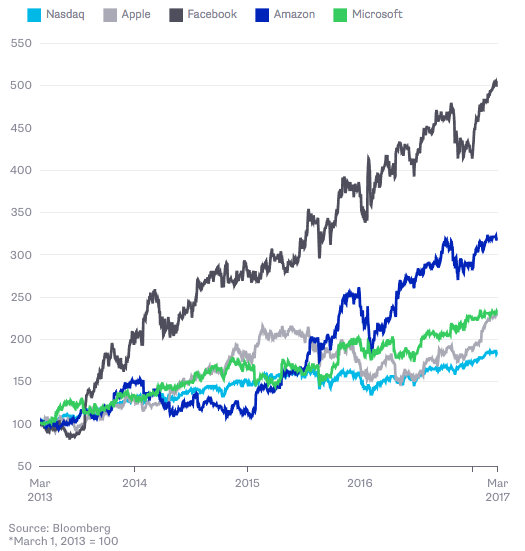

This issue of narrowing markets is a regular concern (see this and this). As stock cycles enter their final phase, markets often show very specific characteristics. The chart below shows what worries some market-watchers:

Recognizing these periods as tops is a challenge for all traders. Paul Desmond of Lowry’s Research has done yeoman’s work analyzing how tops are formed. His paper, “Identifying Bear Market Bottoms and New Bull Markets” won the Market Technicians Association’s 2002 Charles H. Dow Award.

In an email exchange, Desmond noted that “there are always a handful of stocks that grab the headlines, but they typically have little to do with the overall strength of the broad market.” Desmond advises traders to look for “extreme selectivity” — a period of very narrow breadth, when few stocks are participating in market rallies even as the indexes go higher.

Desmond has analyzed every major market top since 1925, looking for consistent warning signs of an approaching bear market. He notes that “in virtually every case the warnings appear as a persistent divergence between the S&P 500 making a series of new highs, while market breadth makes a series of lower highs, showing that stocks are consistently dropping out of the bull market.” This process has lasted anywhere from four months to two years.

If there were a credible argument to be made that the Nasdaq is “top heavy” — if it were being driven only by those handful of megacap companies — the bear case would be stronger. In the past, a narrow market led by few participants was in the final stage of its life cycle. But that’s not what we see at present. Desmond notes that Nasdaq 100 and Nasdaq 500 advance-decline ratios are at new bull market highs. That sort of broad-based market participation isn’t indicative of the end of market cycles. “The bottom line,” Desmond said, “is that there are no significant early warning signs of a major market top at present.”

I am in agreement with Desmond’s bullish outlook, but time will tell if — and more importantly, when — the bears are finally right.

_________

1. As the Wall Street Journal notes, Nasdaq has hit new highs only in nominal terms: “Adjusted for inflation, the Nasdaq Composite is still off 1171.07 points from its March 2000 peak, which is 7196.56 in March 2017 dollars.”

2. I do not want to suggest that valuations never matter. It’s just that for most of a market cycle, valuation concerns are overblown. Toward the end of stock-market cycles, when investors are willing to pay almost any price to own a specific stock, is where we see a lot of damage done by excess valuations. These tend to pull gains forward, from the future into the present. Investors are making a bet that earnings growth will eventually catch up with current share price. What actually occurs is the reverse: Stock prices fall to a level commensurate with recent earnings.

Originally Judging the Staying Power of Record Markets