Bigger Raises Might Be Coming in 2018

Thank tightening labor markets, higher minimum wages and steady growth.

Bloomberg, January 8, 2018

Tight labor markets and rising minimum wages are leading to real pay increases for lots of Americans.

These are two economic trends I have been writing about for the past several years. The tightening job market was one of the hidden stories of the early stage of the recovery from the great financial crisis. Once the unemployment rate fell below 5 percent in early 2016, economists and others began recognizing what was more or less inevitable.

This has helped workers in the middle of the wage distribution, while new laws raising minimum wages are helping laborers at the bottom of the economic strata. 1

Before someone takes credit for these long-standing trends, let’s take a closer look at why wages are rising, and what it might mean for the broader economy.

Let’s begin with the minimum wage. For the past 10 years, labor organizers have been advocating for a national minimum wage of $15 an hour. Although they have been unsuccessful at the national level — the federal minimum wage has been $7.25 since 2009 — they have achieved significant increases at the state and city level. In 2018, 18 states have (or are scheduled to) raise their minimum wages. In addition, 22 cities will similarly raise wages.

The strongest argument in favor of raising the minimum wage nationwide is that it has failed to keep up with inflation and productivity. Had it done so, minimum wages would be at $11.62 or $19.33, respectively. The strongest argument against is that the country is really a collection of smaller, varied regional economies; by definition, some are much more prosperous than others. It shouldn’t be shocking to say that poorer areas cannot be expected to pay the same wages of richer states and cities.

But here’s what’s interesting about areas that can justify rising minimum wages: First, there is a modest increase in wages across the lower end of the pay scale. It is more than just the minimum-wage workers seeing their pay rise; the more senior employees who were previously getting more than the minimum suddenly find themselves at parity with newer, junior employees. They often request increases to compensate for this — or switch jobs for higher pay.

Second, wage increases typically lead to a modest uptick in the local economy. Theoretically, this leads to more job gains, and a virtuous cycle. Despite forecasts of doom and rising job losses, higher minimum wages have gone hand in hand with improving conditions in cities such as Seattle, Portland and San Francisco. 2

In other word, whether minimum wages have increased because of legislation in your state or city is almost irrelevant in markets with little labor slack. As we noted last year:

With unemployment now less than 5 percent, employers are finding themselves with fewer hiring options … Rising salaries are one reason for the increased participation rate, as the prospect of better pay draws more people into the labor force. As much as employers want to hold the line, competition for workers is intense, with market forces helping to drive wages higher.

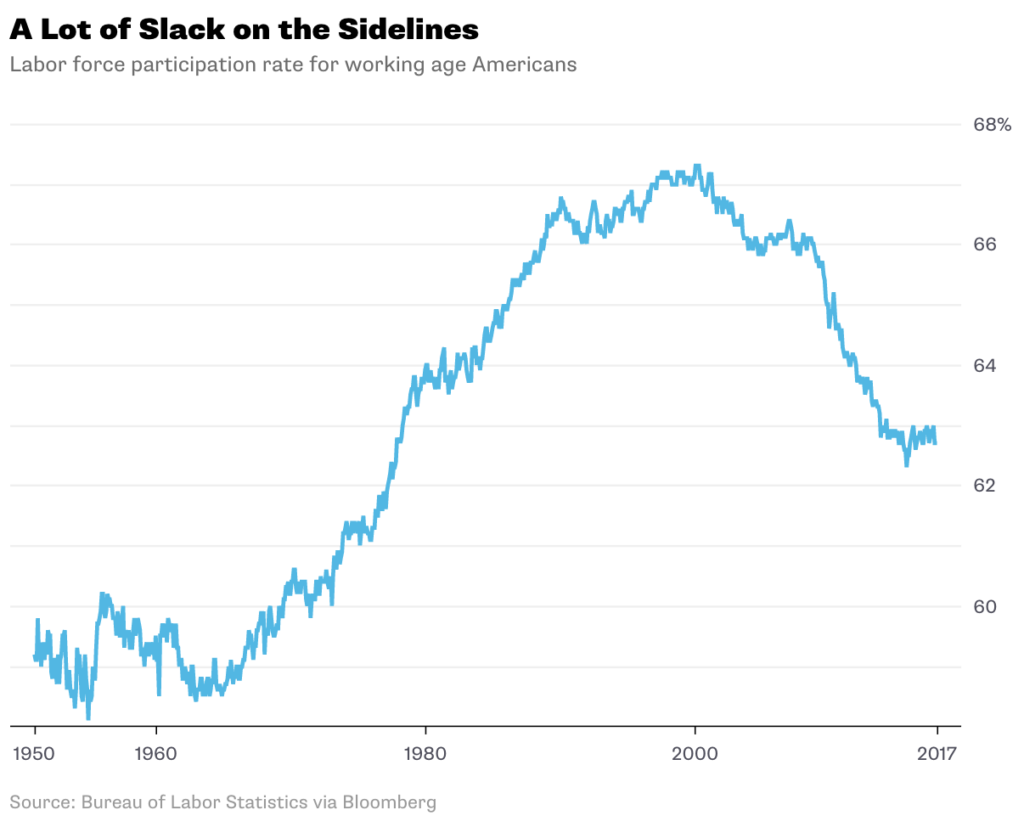

That was written when unemployment was 4.8 percent; today, it is 4.1 percent. You have to go back to the tail end of the dot-com era to find a lower rate (the lowest was 3.8 percent in April 2000), although the rate was lower during some parts of booms in the 1950s and ’60s. This leaves employers who need to hire with two options. One is to entice employees from the competition with promises of better working conditions, wages, stock options, benefits, perks and so on. The alternative is to find ways — again with higher pay and the like — to bring those who have left the labor force back into the fold. This latter option may be the more intriguing: The labor force participation rate of 62.7 percent of working age Americans is at lows not seen since the late 1970s, but for the past couple of years has shown signs of bottoming.

Either option requires employers to spend more, and in some fields, considerably more, on employee compensation.

Thus, what we are starting to see in the broader economy is the culmination of several trends that date back to 2010 or so. Hourly average wages were up last month at an annualized rate of 2.5 percent. Don’t be surprised if that rises faster as the economic recovery from the financial crisis continues apace.

The biggest impact of wage gains will play out for investors in several ways:

• First, expect to see costs rise for companies. With profits at record highs and labor costs fairly modest, some mean reversion is inevitable. How that will affect profits has yet to be determined.

• Second, count on increases in retail spending, durable purchases and even homebuying. The early data from the holiday shopping season shows Americans are in a spending mood.

• Third, and perhaps most important, is the impact on inflation. There are some early signs that wage inflation is rising, and could push through to overall prices. This could have implications for how quickly the Federal Reserve raises interest rates.

The decline in unemployment and rise in minimum wages are the culmination of years of earlier patterns; watch for how they unfold in 2018.

_______

1. A large swath of wage earners at the top of the scale — especially workers in science, technology, engineering and mathematics — are benefiting from a shortage of qualified people. Planned limitations on admitting qualified immigrants will create shortages in these areas, leading to much higher wages.

2. These metropolitan areas, and other coastal cities and states, have been experiencing a robust economic expansion because they are hubs for hot industries. It is difficult to tease out the precise effects of the minimum wage, as growth could easily have come despite, rather than because of, the minimum wage increase.

Originally: Bigger Raises Might Be Coming in 2018