Don’t Like Trump? Your Financial Analysis Might Be Biased

Partisanship should have no place in a corporate-credit rating. A new study says it does.

Bloomberg, December 3, 2018

The dangers of political bias for investors has long been one of my favorite rants. Politics is tribal, opinionated and typically one-sided. These are emotional hot buttons that lead to biased thinking. And as we have learned from both behavioral finance and decades of experience, those affectations are the enemy of good returns and smart investing.

As a reminder, partisans warned us that if Donald Trump were elected president, the market would tank. (It didn’t). Instead the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index rose 37 percent, from Election Day to its September 2018 peak. And recall the warnings that Trump’s predecessor, variously described as a socialist, Kenyan or Muslim, was “killing the Dow.” (He didn’t). Instead, the Dow Jones Industrial Average more than doubled during the eight years of Barack Obama’s presidency.

Despite the obvious lessons, admonitions to investors to keep their politics out of their investing seems to fall on deaf ears.

Now, thanks to a recent study 1 reported on by my Bloomberg News colleague Sarah Ponczek, we learn that partisan bias also affects the decision-making processes of financial analysts as well. Elisabeth Kempf of the Booth School of Business at the University of Chicago, and Margarita Tsoutsoura of the SC Johnson College of Business at Cornell University, looked at corporate-credit ratings relative to analysts’ political leanings. The results strongly imply that regardless of the quantitative aspects of credit ratings, subjectivity still brings with it the usual human errors of bias and lack of objectivity.

This should come as no surprise. Analysts are (for the most part) only human, and therefore, affected by the usual human behavioral errors and cognitive foibles. The ones who are not human are algorithms, and they have yet to replace the world’s financial analysts — and it may well be that they end up reflecting the biases of their human designers.

According to the study, “Partisan bias affects decisions . . . Analysts who are not affiliated with the U.S. president’s party are more likely to downward-adjust corporate credit ratings.” The differences are not insignificant: analysts who are not in the same political party as the president tend to lower their bond ratings by “0.015 notches more than someone from the same side of the [political] aisle each quarter.”

This accounts for almost 10 percent of the total change in ratings.

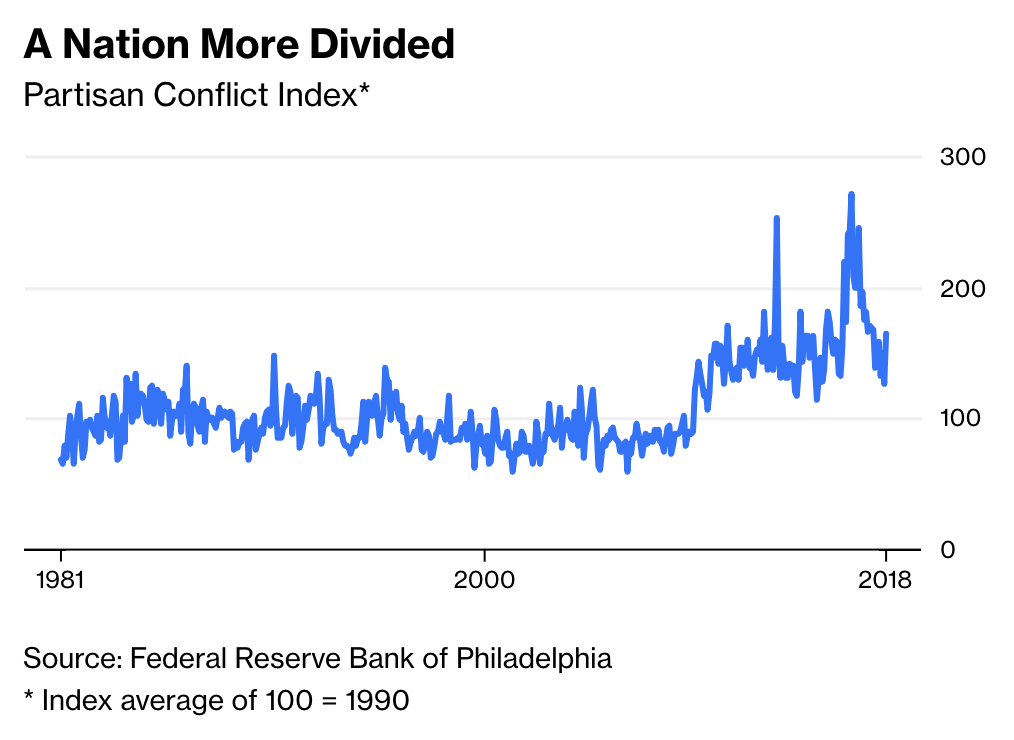

As Ponczek notes, “The connection also grows during election quarters and among analysts who are more politically active.” How much more? During periods of elevated political disagreement, 2 the impact of political bias is shown to be a good deal larger. Using the Partisan Conflict Index of the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, the authors of the study found increased political disagreement can make the impact of bias on ratings as much as 75 percent larger. This is a not insignificant shift.

This is yet another reminder that people come with an assortment of emotional baggage and intellectual infirmities that are not an occasional error, but are hard wired into our approach to just about everything. If something as mundane as corporate-credit ratings can be influenced by partisan affiliations, then what isn’t influenced by our flawed powers of intellect and reasoning when we’re not looking?

The CFA Institute, which trains and certifies most financial analysts in the U.S. (and quite a few who end up overseas), offers a behavioral finance component to its training regimen, according to a several CFA charter holders I spoke with. And there seems to be plenty of emphasis on maintaining a degree of objectivity in the CFA ethics section.

Regardless, given the results of this study, it might be time for the institute to further emphasize the issue of bias — partisan or otherwise — in anyone’s analysis.

As if we need any further reminders: everybody who is born with the Human 1.0 wetware is subject to an array of forces that work to compromise their objectivity. From cognitive errors to the deepest psychological tendencies, we are all at risk of allowing our hard-wired behaviors to affect our decision-making. A little enlightened self-awareness coupled with attempts to avoid our own worst tendencies can go a long way to help us to manage this aspect of our behavior.

At the very least, it gives one a strategic advantage over those who do not.

_________

1. “Partisan Professionals: Evidence from Credit Rating Analysts” by Elisabeth Kempf, Margarita Tsoutsoura NBER Working Paper No. 25292, November 2018

2. Page 22: “To measure partisan conflict, we use the Partisan Conflict Index provided by the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia. The index tracks the degree of political disagreement among U.S. politicians at the federal level by measuring the frequency of newspaper articles reporting disagreement in a given month.

~~~

I originally published this at Bloomberg, December 3, 2018. All of my Bloomberg columns can be found here and here.