Fans and Foes of Buybacks Aren’t in Disagreement

As a group, companies that repurchase shares are good investments even as individual companies squander their money.

Bloomberg, November 30, 2018

There is an inherent tension between those favoring and opposing corporate stock buybacks. Today let’s see if we can reconcile the views of the two groups, finding a middle ground.

Those who favor share repurchases point out that they are no different from dividends from a balance-sheet perspective — it is a way to return cash to shareholders. Those buybacks reduce the total number of shares used in earnings per share calculations. Companies that buy back shares find their way into equity screens that outperform as a group. Anywhere you can find market-beating alpha is a win.

Those who are less enamored of buybacks point to individual companies as counterpoints. Many high-profile corporations do an awful job in the timing of their buybacks. They tend to buy in an effort to prop up share prices, which end up falling anyway. One complaint is that cash could be better used, starting with saving for a rainy day. Another valid criticism is made of those companies that borrow money in order to finance buybacks. Meanwhile, it has long been a complaint that repurchases are an expensive way to hide the impact of dilutive stock-option compensation plans; many of these plans serve to lavish corporate executives and other insiders with grossly inflated pay.1 Last, buybacks do not seem to be innovative; this is a critical issue for those companies in competitive industries that need to use their finite capital efficiently for expanding,improving existing products or developing new ones .

If you are going to redistribute capital to shareholders, there is a case to be made that the better choice is to return cash to investors via dividends. To buy back stock is to rely on the market-timing skills of conflicted, self-interested managers. Cash can be put to use any way an investor sees fit, whereas a buyback that reduces the number of shares outstanding only raises earnings per share, all things being equal.2 The flexibility of cash in hand beats the uncertain prospect of higher EPS for most investors.

So from the standpoint of the money manager, buybacks can help identify certain types of stocks that might be worth buying. Yet from an individual stock’s perspective, it can be an indicator of poor management.

Let’s dig deeper and go from the specific to the general.

For any individual company, there is a beggar-thy-neighbor element to share repurchases: Companies that buy back shares raise their EPS versus those that don’t. Collectively, companies doing buybacks look better, over both the short and medium term. It is a relative advantage, though not necessarily an absolute one.

Said differently, buybacks do create value, by reducing share count and raising EPS, at least relative to those that don’t or can’t do buybacks.

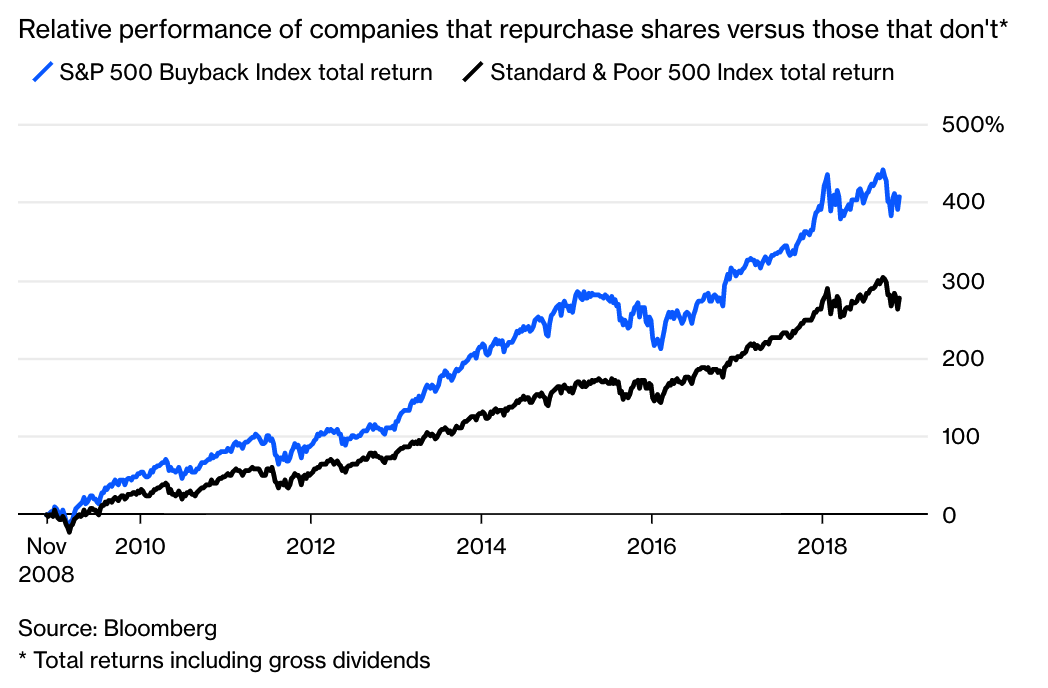

As an example, look at the chart below of the S&P 500 Buyback Index. These are the top 100 stocks in the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index based on their buybacks.3 They have as a group significantly outperformed the broader index during the past 10 years.

Consider also that these companies doing buybacks tend to look more like value investments than growth stocks. That makes this outperformance even more impressive during a decade when growth has trounced value.

I don’t want to sully this analysis too much by cherry-picking anecdotes — I already did that here. With each side of the debate seeming to make very different points — they are arguing past each other — let’s get on with the exercise of trying to reconcile the pro and con arguments.

The pro-buyback camp look at markets from a 30,000-foot perspective. The advocates correctly note that buybacks are a useful tool for identifying those companies that have higher probabilities of outperforming markets. Screening for buybacks works to the advantage of investors by finding companies with healthy cash flows and a commitment to returning that capital to shareholders.

The antibuyback group tends to be offended by the most egregious and self-serving buybacks. These turn out to be done by businesses that are not well-managed to begin with. These companies often have squandered their competitive advantage, using their limited capital for share repurchases when perhaps they might have been better served spending the dollars elsewhere, such as on research and development. General Electric Co. and General Motors Co. come to mind; perhaps even Apple Inc., which may be the biggest spender on buybacks, fits this bill.

Thus, there really is no disagreement — collectively, buybacks enhance performance. But on a company-by-company basis, investors need to be on the lookout for buybacks that substitute for good decision-making by management. This is especially true in hyper-competitive industries where there are existential threats to a company’s survival. This is surely the case for both GE and GM, and , maybe even for Apple.

The bottom line is this: screening for share repurchases helps to identify potential outperformers versus nonpurchasers. However, corporate management that buys back stock often discovers too late that there were much better uses for their capital. The list of companies belatedly learning this is sure to keep growing.

__________

1. There’s also the issue of whether companies and the economy would be better off if managers used cash for raising worker pay rather than buybacks. That’s a different and worthy debate I shall leave to others.

2. Dividends give an individual shareholder more flexibility; capital returned can be reinvested in the company’s stock if that’s what its owner chooses.

3. Methodology: The S&P 500 Buyback Index measures the performance of the top 100 stocks with the highest buyback ratio (cash paid for common shares buyback in the last four calendar quarters divided by the total market capitalization of common shares) in the S&P 500.

It is equal weighted across all 100 holdings. It gets rebalanced quarterly, except for major corporate actions, such as mergers and spin-offs; companies can only be added to the index during the quarterly rebalancings.