Tail Risk: Part 1, The Persistent Effects of the Great Recession

by Julian Kozlowski

The Great Recession of 2007-09 was a deep downturn with long-lasting effects on credit markets, labor markets, and the aggregate economy. This recession differed from previous ones, however, because (1) the downturn was more extreme and (2) it generated long-lived effects in the economy. Perhaps this recession has had more persistent effects because it had been perceived as an extremely unlikely event. Many of us now question whether the Financial Crisis could repeat itself. Today, financial panic is a new reality that may be affecting the aggregate economy.1

One of the consequences of the Great Recession is a change in perception: Such a large negative shock to the economy was unexpected (if not completely dismissed); and now we may expect (or at least believe it is more probable) that a similar event might occur. In short, the Great Recession caused a change in “tail risk.”2 In this three-part series, I explore how changes in tail risk can affect the aggregate economy. Part 1 explains how the Great Recession made us reevaluate the way we think about tail risk. Part 2 explores its consequences for the economy and discusses why an increase in tail risk can help us understand the slow recovery after the Great Recession. Part 3 shows how the decline of the risk-free rate might be a consequence of the increase in tail risk.

Why focus on tail risk? Perception can be everything: People observe new events and use them to inform their probability estimates. For example, if you haven’t seen many bank runs, you think bank runs are very rare. However, when you see a bank run, you update your estimates and determine that bank runs are not as rare as you previously thought. As an analogy, imagine you see the outcome of many rolls of a die. You don’t know how many sides the die has or if the sides are weighted. However, you’ve seen numbers one through six come up many times, about equally, so you think this is a standard six-sided die. One time, though, a seven comes up. As a result, you revise your belief about this die and now think the die has at least seven sides. Even if you don’t see a seven again, the knowledge that the number seven can be rolled stays with you. It would probably affect your willingness to bet on the outcome of a die roll, too. Seeing the Financial Crisis was like seeing a seven come up on what you thought was a six-sided die.

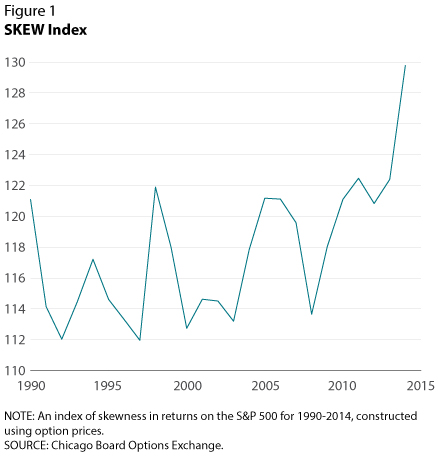

Did tail risk or the perceived probability of a financial crisis increase after the Great Recession? There is evidence supporting the hypothesis that it did. Figure 1 shows an increase in tail risk as measured by the Chicago Board Options Exchange SKEW Index (SKEW). SKEW is an index of tail risk in the S&P 500 constructed using option prices, and larger values of SKEW imply higher tail risk.3 Figure 1 shows a clear rise since the Financial Crisis, with no subsequent decline.

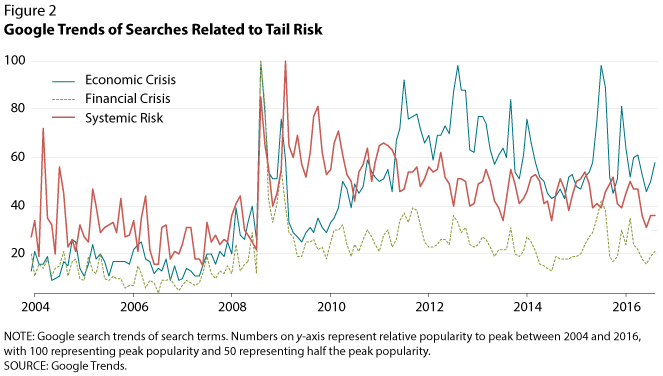

Google search trends also show evidence of an increase in tail risk after the Great Recession. That is, in using Google to look at the search frequency of terms related to tail risk, such as “economic crisis,” “financial crisis,” or “systemic risk,” we can see these searches rose during the crisis and never returned to their pre-crisis levels (Figure 2).4

In Parts 2 and 3 of this series, I will show how this increase in tail risk has had large real economic costs and has affected the return on safe and liquid assets.

Notes

1 These ideas are analyzed in Kozlowski, Veldkamp, and Venkateswaran, 2016; Shiller, 2017; and Shiller, 2018, among others.

2 Tail risk is the risk that the economy will suffer extreme negative shocks, more than two standard deviations from the mean.

3 A value of 100 means the distribution of prices in the S&P 500 is perceived to be the normal distribution. If the index is above 100, then the distribution is attaching more weight to the left end of the normal distribution curve. For more information, see http://www.cboe.com/micro/skew/introduction.aspx.

4 People will acquire more information about an economic or financial crisis if there is an increase in tail risk. Hence, an increase in tail risk is associated with an increase in the frequency at which people search these terms on Google.

References

Condon, Bernard. “AP Impact: Families Hoard Cash 5 Yrs After Crisis.” Associated Press, October 6, 2013.

Kozlowski, Julian; Veldkamp, Laura and Venkateswaran, Venky. “The Tail That Wags the Economy: The Origin of Secular Stagnation.” VOX, September 11, 2016.

Shiller, Robert J. “The Economy Is Stagnant Because People Fear for the Future.” The Guardian, May 23, 2017.

Shiller, Robert J. “Why Our Beliefs Don’t Predict Much About the Economy.” New York Times, October 12, 2018.