Who Pays the Tax on Imports from China?

Matthew Higgins, Thomas Klitgaard, and Michael Nattinger

Liberty Street Economics, NOVEMBER 25, 2019

Who Pays the Tax on Imports from China?

Matthew Higgins, Thomas Klitgaard, and Michael Nattinger

Tariffs are a form of taxation. Indeed, before the 1920s, tariffs (or customs duties) were typically the largest source of funding for the U.S. government. Of little interest for decades, tariffs are again becoming relevant, given the substantial increase in the rates charged on imports from China. U.S. businesses and consumers are shielded from the higher tariffs to the extent that Chinese firms lower the dollar prices they charge. U.S. import price data, however, indicate that prices on goods from China have so far not fallen. As a result, U.S. wholesalers, retailers, manufacturers, and consumers are left paying the tax.

Going Up

In August 2017, the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) announced that it had launched an investigation to determine whether Chinese policies related to technology transfer and intellectual property were actionable under the Trade Act of 1974. In April 2018, USTR announced its finding that these policies “are unreasonable or discriminatory and burden or restrict U.S. commerce.” A number of trade actions against Chinese goods have now been announced. The first tariff increase came in July 2018, and was followed by a sequence of further hikes as the trade dispute continued. By June 2019, according to the USTR estimate, some $250 billion in Chinese goods faced an additional tariff of 25 percent. Another round of sharp increases was announced in August but these moves have been largely postponed. However, an estimated $120 billion in additional goods were hit with a tariff hike of 15 percent in September.

Tariffs are collected at the port of entry by the U.S. Customs, with the duty paid by the immediate U.S. purchaser of the good. In effect, the U.S. purchaser pays a sales tax to the Customs Service for the right to import the good.

No Clear Change in Import Prices

Who ends up bearing the burden of the higher tariffs? Chinese firms could lower the prices they charge to offset the tariff hikes in order to avoid losing market share in the United States. For example, a 25 percent tariff hike would need to be offset by a 20 percent price cut by the Chinese supplier to leave the total cost to the U.S. importer firm unchanged (1.25 x 0.80 = 1.0). Chinese firms will be more prone to lower prices to the extent that they believe U.S. purchasers can either do without their products or find alternatives from other suppliers.

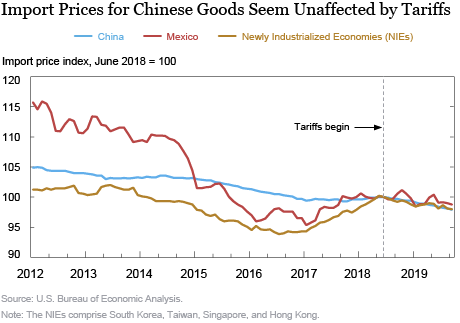

A May 2019 Liberty Street Economics post noted that prices on imports from China have been stable in the face of higher tariffs. This stability has continued in the face of further tariff hikes. As seen in the chart below, prices on goods from China fell by only 2 percent in dollar terms between June 2018, just before the first tariffs were imposed, and September 2019. (These data refer to the prices charged by Chinese suppliers and do not include tariff expenses.) This drop is a small fraction of the amount required to offset the increase in tariff rates. Moreover, prices on goods purchased from Mexico and the so-called Newly Industrialized Economies (South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, and Hong Kong) have fallen by roughly the same amount, suggesting that this small drop is the result of general market conditions rather than the increase in tariffs.

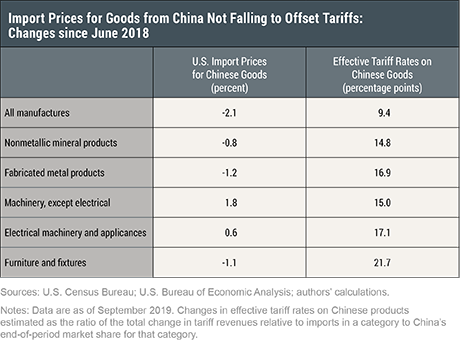

The same pattern is evident when we look at disaggregated import price data. The table below shows how much import prices for goods from China changed between June 2018 and September 2019 in several manufacturing sectors. The table also shows an estimate of the percentage point increase in the average tariff rate on Chinese goods over this period.

For these product categories, price changes for goods from China have been very small relative to the jump in tariff rates. Note that changes in tariff rates on electronics and computers had been modest as of September.

Why Haven’t Import Prices Fallen?

Policy efforts since World War II have been focused on lowering trade barriers. As a result, economists don’t have much data from which to glean insights into how firms respond to tariff hikes. Potential explanations for why import prices appear unaffected thus far include:

- Narrow profit margins: Offsetting a large rise in tariffs by accepting lower profit margins isn’t possible if margins are already thin. Many of these firms may be dropping out of the U.S. market.

- Few competitors: Chinese firms with few non-Chinese competitors will feel little pressure to adjust, leaving the tariff burden to the U.S. buyer. In textbook terms, these firms face a low price elasticity of demand.

- Intra-firm imports: Affiliates of multinational corporations may be leaving reported import prices unchanged for accounting reasons. In doing so, the multinational would be letting higher tariffs reduce the reported profits of its U.S. operation (rather than those of its Chinese operation).

- Price contagion: Lowering U.S. prices could cause customers in other countries to demand similar discounts.

The Role of Exchange Rates

Some observers have argued that the depreciation of China’s currency against the U.S. dollar is shielding U.S. businesses and consumers from the impact of the tariffs. In fact, the renminbi has fallen by about 10 percent versus the dollar since U.S. trade actions were first announced in April 2018.

The weaker Chinese currency provides scope for Chinese firms to lower their dollar prices. Each dollar of revenue is now worth more in local currency terms, and that matters since Chinese firms’ costs are predominantly in renminbi. But the facts we’ve reviewed show that Chinese firms have not used the change in exchange rates to regain some of the competiveness lost from tariffs by lowering their prices in dollar terms. Instead, they’ve accepted the loss in competitiveness in the U.S. market and have used the weaker currency to pad profits on each unit of sales.

What Happens if Import Prices Don’t Fall?

The continued stability of import prices for goods from China means U.S. firms and consumers have to pay the tariff tax. In annualized terms, U.S. tariff revenues were roughly $40 billion higher in the third quarter of 2019 relative to the second quarter of 2018, before the China-specific tariff hikes. This is considerably below what might have been expected. USTR estimates had a tariff hike of 25 percentage points on $250 billion of Chinese goods as of June, pointing to a $62 billion increase in annualized revenues. (The additional tariff hike imposed in September would push this figure higher.) The shortfall in duties is largely due to a steep drop in purchases of the affected goods. Detailed data show imports of goods hit by tariffs have declined by an annualized $75 billion since the second quarter of 2018, while imports of non-tariffed goods have been roughly stable.

Who pays the tariff tax depends on how it is split between lower profit margins (for wholesalers, retailers, and manufacturers) and higher prices for consumers. Estimating this split is difficult since the distribution of any tax increase on profit margins and prices depends on the details of market structure, such as the number and size of competing firms.

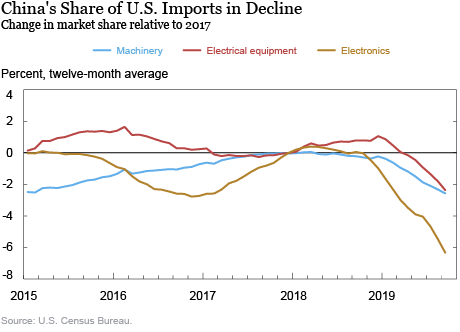

Regardless of whether consumers or businesses bear the burden, sustained high tariffs on Chinese goods will encourage a search for alternative suppliers. The chart below shows the change in China’s share of total U.S. imports by product category relative to 2017. China’s market share has already fallen by roughly 2 percentage points for machinery and electrical equipment and by close to 6 percentage points for electronics. A broader look at the trade data shows that China’s lost market share has gone largely to Europe and Japan for machinery and to Malaysia, South Korea, Taiwan, and Vietnam for electronics and electrical equipment.

To be sure, these figures will somewhat overstate the immediate hit to China’s economy. Trade data attribute all value added to the last country in a multi-country supply chain. Recent data from the OECD show that about 20 percent of the value of China’s manufacturing exports originates in other countries, principally other economies in the Pacific region. Moreover, companies may be shifting the final stages of production for Chinese products to third countries to avoid the tariffs.

Source: Liberty Street Economics