Source: Carl Richards, Behavior Gap

Yesterday’s column, not surprisingly generated email from investors who disagreed with my criticisms on market timing. They came primarily in three flavors:

1. “It is not timing if you are engaging in risk management”

2. You do it (and write about it)

3. What specifically was wrong with that re-allocation?

A few words on each:

“It is not timing if you are engaging in risk management”

Selling equities with the intention to repurchase them later at a lower price is the definition of market timing EOM.

Do not confuse this with a change in your asset allocation relative to your time horizon and tolerance. For most investors, that is risk management. Your financial plan has goals (e.g., retirement, purchasing a home) and when you are 3-5 years away from that goal, a reduction is risk asset percentage is sensible risk management.

But please do not lie to yourself: A change in allocation on a temporary basis to capture price fluctuations during periods of elevated volatility is market timing, plain and simple.

You do it (and wrote about it)

I have on occasion bought extreme selloffs and sold stocks at what I thought was the peak with the intention of capturing the next market move as a trade. But there are enormous differences between the breadth, scale, and asset location of those — trading a small portion of my” fun money” account on big disruptions like we saw in March. Compare that with the sort of fear-based MacroTourism we tend to see whenever there is a selloff and recovery. And

I have decades of experience analyzing sentiment, technicals and quantitative data, and despite all of that, I still believe it all comes down to “market feel.” This is why the $1.5B at RWM is NOT managed this way; I would not want to play with people’s real money this way. And don’t kid yourself, market timing is mostly playing.

What specifically was wrong with that re-allocation?

The mistake I specifically referenced in the column was described thusly:

“I was reminded of the risks of timing recently via column by my Bloomberg Opinion colleague Farnoosh Torabi. Last month, Torabi explained why she was reducing her equity exposure from 81% of her portfolio down to 60%, as she tripled her fixed income holdings to 27% in her retirement accounts. For a variety of reasons, not least of which is her age – she has decades before she retires – I would have advised her against those actions.”

That is what generated the most pushback.

The Mistake: Let’s look at a classic mistake made by someone who admittedly knew better: It was July, the markets had recovered strongly, even as the economic fundamentals looked terrible. This is the perfect scenario for an investor to allow their emotions to get the best of them, leading to a classic investing error.

Lay people can turn off the market news, but financial journalists like Farnoosh Torabi (or as an emailer suggested, Clive Crook) cannot. In her career as professional writer that she is immersed in a never-ending stream of often terrible news, commentary and analysis about markets and the economy. It is an occupational hazard.

If she were a 65-year old, nearing retirement in a few years, I could endorse that move as good (actual) risk management. But she is a 40-year old professional with at least 20-30 years before retirement. Add to that by 2050, when she hits 70-years old, human life expectancy might offer her as much as another 30 or 40 years longer to live. Her money may have to last a good long time, and bonds yielding 1% are not going to get it done.

Since she made her sale, the S&P500 has risen >5%; but we don’t want to engage in “resulting,” e.g., focusing on the outcome as opposed to the process. Instead, we need to consider the probabilities. Markets just made an all-time high, and as my colleague Michael Batnick observed, the data shows that “all-time highs are nothing to fear. Returns are actually higher 6, 12, and 24 months out. Rising prices attracts buyers, it’s that simple.”

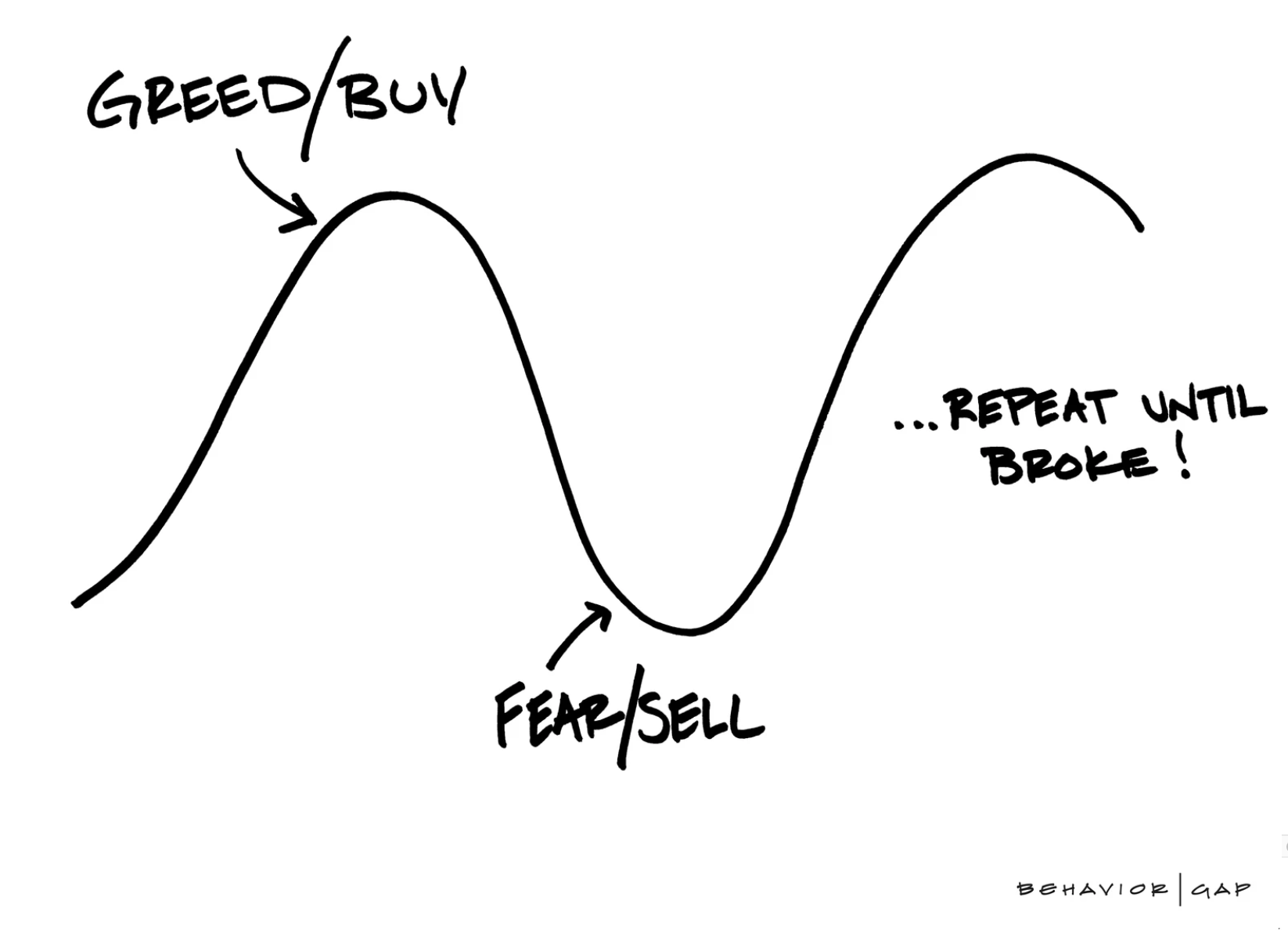

What happens to an investor who sold and then the market keeps going higher? How do they get back in? What we observe typically is that as prices rise, people who have lowered equity exposures become emotional about missing out. FOMO eventually panics them back in and usually at the worst possible time – just before a periodic (and normal) drop that occur so frequently. That leads to more trading, worse performance and even more financial damage.

All because of macro-toursim: being “concerned about the fundamentals of our economy” despite having any real model to objectively evaluate said economy. Never mind that the economy and the stock market are not especially correlated, or that the worst sectors of the economy hardly matter to the big stock market indices.

The good news is her market timing was in a qualified (e.g. taxable) retirement account. Otherwise, those 28% gains she earned over the past two years would have been taxed at either 15%, 20% or 23.4%, long term, or at her personal tax bracket short-term (depending upon when she made those purchases, and what her tax bracket is). As a New Jersey resident, she would have paid another 9% in cap gain costs.

Most people are not built for market timing. It requires too much contrarianism, emotional discomfort, and self-discipline. Most of us are not especially honest with ourselves: We are all too happy to share our memorable wins, while indulging our selective retention on our losses. All traders do this, but the smarter ones are brutally honest with themselves, objectively reviewing a spreadsheet of wins and losses so as to make improvements.

Previously:

Capitulation? Hardly (July 11, 2006)

Curse of the Macro Tourist (July 25, 2015)

The travels and travails of the macro tourist (Washington Post. July 18, 2015)

DOs and DONTs of Market Crashes (January 16, 2016)

Watching From Afar (March 2, 2020)

Don’t Panic! with apologies to Douglas Adams (March 9, 2020)