Is the Stock Market Overvalued, Cheap or Just Right? A Debate

Valuation metrics can help in investment decisions, but they’re also subject to misuse and misinterpretation.

By Nir Kaissar and Barry Ritholtz

Bloomberg, July 9, 2020

Most discussions about the stock market eventually get around to the question of valuation: Are shares prices too high, too low or just right? But valuation may not offer the answers investors want to hear. Bloomberg Opinion columnists Nir Kaissar and Barry Ritholtz recently met online to debate.

Barry: “Value” as a measure of cheapness or expensiveness of a long-term portfolio means much less than many people imagine.

That sounds controversial, but it should not be. “Stocks are pricey, overvalued, and prone to crash” is something I have been hearing for as long as I have owned or traded securities, for more than 25 years, going back to the early 1990s.

Valuation measures are not useless – they just are not the “be all” metric many believe. Valuation can give you a rough range of future expected returns, but even that is only a broad estimate. Some people use the phrase “Fair value” as a way of describing the overall market (or a specific stock) that is priced appropriately. But in reality, “Fair value” is a level that markets tend to careen past on their way to becoming incredibly cheap or wildly expensive. It is not a point where equities ever spend much time.

Meb Faber, of Cambria Investments, observes “While buying expensive markets generally will produce lower future returns, you will have positive outliers. The same for cheap markets, it’s usually a good idea but they can always get cheaper.”

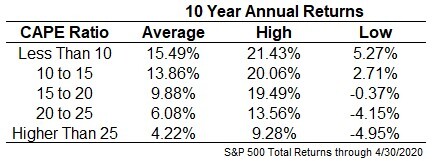

My colleague Ben Carlson went even further, pointing out that the averages can be misleading, by showing the broad range of possible outcomes based on Shiller’s cyclically adjusted price to earnings ratio (CAPE). Sometimes low CAPEs yield mediocre returns; other times expensive CAPE generates good to very good returns.

Source: Ben Carlson

Here is a radical statement: For much of the past three decades – essentially my career in finance – valuation measures have not been a useful guide for buying, selling or even just holding equities. Even worse, the way most investors use it is inappropriate, and they hurt themselves trying to time the market (poorly) or justify holding onto to something they should have long ago sold.

Valuations do matter – just not as much or in the way many people believe.

~~~

Nir: I would argue that valuations matter more than people realize. If used properly, valuation is among the most powerful tools available to investors.

Here’s why: Most financial decisions require an estimate of future returns from investments. That estimate is necessary, for example, for deciding how much to save for retirement or kid’s college, whether to make extra mortgage payments, how to spend sustainably during retirement, or how to construct a portfolio. The problem, of course, is that no one can predict the future. So the question is what is the most reliable way to estimate future returns.

This is where valuation comes in handy. There’s a strong correlation, for instance, between the U.S. stock market’s valuation, as measured by earnings yield in this example (inverse of the famed price-to-earnings ratio), and subsequent returns. That is, high earnings yields have historically signaled higher future returns, and vice versa. From 1881 to June 2010, the longest period for which numbers are available, the correlation between the S&P 500 Index’s earnings yield and its subsequent 10-year total real return was 0.56, counted monthly. That’s based on cyclically adjusted earnings, but the correlation is similar using other measures of earnings.

And contrary to popular perception, valuation has been even more reliable in recent decades. The correlation spiked to a near-perfect 0.94 from 1990 to 2010. Why? High earnings yields during the stagflation of the early 1980s were followed by a two-decade bull market. Then, low earnings yields during the dot-com mania of the late 1990s were followed by a lost decade for stocks. And most recently, high earning yields during the 2008 financial crisis were followed by one of the strongest bull markets on record.

Valuations are similarly useful for gauging future returns from bonds and other stock markets. There are some important caveats, though. While valuation is a useful tool for estimating returns over a reasonably long period, it tells you nothing about the path. It can’t tell you if or when markets will crash or how they’ll perform in the near term. Anyone using it for those purposes is likely to be disappointed, as you rightly point out.

Also, a strong correlation isn’t a perfect one, which means that valuation will be wrong some of the time. But it’s demonstrably better than naively assuming, as many investors do, that future returns will resemble those of the past. Often, it’s just the opposite.

~~~

BR: For reasons we explore below, average equity valuation has risen during the past century. Because of this, many investors, overly sensitive to valuation metrics, were scared off of some of the most lucrative investments in history. This is a reminder that no single metric should be considered alone, and needs to be put into proper context. Interest rates, inflation, innovation, creative destruction, all matter to equities.

Consider the history of corporate America: Companies previously required men, materiel and an enormous amount of capital. Think about the 1,000s of square miles of land railroads had to purchase, then forge and lay steel tracks. That’s before building locomotives, buying coal, hiring engineers, etc. Steel plants had to build foundries, Auto manufacturers had countless different specialties — engines, glass, interiors, body designs, electronics, tires, braking systems, etc. All of these were tremendously capital intensive activities.

To attract capital, companies HAD to be cheap. Otherwise, it would have been difficult to generate any sort of sufficient return. Today, it takes a few founders, a couple of laptops, and access to Amazon Web Services to launch an enterprise. Recall in 2012, the Facebook purchase of Instagram for a billion dollars. Back then, Insta had a few dozen employees but was adding mobile users like crazy.

Should 20th century and 21st century companies be similarly valued? The first expensively assembles atoms into a final product; the second inexpensively manipulates bits in the digital realm. Of course you are going to pay more for the latter than the former.

Factories have some economies of scale, but nothing like the potential to scale digitally. To get investors to commit capital, the physical world of atoms must be cheaper relative to the digital universe — and most of the time, much cheaper.

It is not just companies — purchasing a stock today is so much cheaper and easier than it was last century. The massive frictions to stock purchasing equities made the entire activity more expensive — stocks were somewhat cheaper to compensate.

How should investors calculate the change in what valuation they should be willing to pay for equities given this changing corporate and landscape?

~~~

NK: I agree that companies have generally become less capital intensive over time. It’s also clear that trading costs are far lower today than they used to be. But the impact of those changes on valuation is less clear.

It’s true that the U.S. stock market has generally been more expensive in recent decades than previously. Going back to my prior example, the cyclically adjusted earnings yield for the S&P 500 averaged 7.6% from 1881 to 1994. Since 1995, however, it has averaged just 3.9%.

Is that the work of leaner capital structures and lower trading costs? Hard to say. First, those trends began well before 1995, and yet valuations were higher in the 1970s and 1980s than during the two decades that preceded them. Second, the period since 1995 happens to include two historic asset bubbles – the dot-com and housing bubbles – that pushed valuations higher. Third, recency bias may be exaggerating the importance of the last two decades, even though they represent only a small fraction of the historical record. And finally, there’s little evidence that evolving capital structures and lower trading costs have boosted stock valuations in other countries.

Fortunately, it doesn’t matter. Investors have no ability to control valuations or predict where they’re going, so what’s driving them isn’t particularly important. Also, most investors should have some allocation to stocks regardless of valuations as part of a broadly diversified portfolio, and they should never blow out of them entirely because they think valuations are too rich. The evidence is overwhelming that all-in-all-out market timing is doomed to fail.

And regardless of what’s driving them, valuations are still a useful gauge of longer-term returns, as I noted previously. They’re also useful for taming investors’ demons. If you’re tempted to chase stocks in a hot market, low earnings yields are a good reminder that it’s probably not worth it. Inversely, if you’re tempted to dump stocks during a crisis, high earnings yields are a good reminder that staying in your seat can be rewarding. And for brave and disciplined investors, modestly adding to their stocks when yields rise and trimming them when yields fall may boost their returns modestly over time.

~~~

BR: Those are all persuasive points. We broadly agree about much of this, but I suspect using very different analyses.

The concern I keep coming back to is the issue of how valuation can be used as a reason NOT to own stocks. Valuations are less significant to me in the investment decision-making process than I suspect it is to you. The primary reasons for this are the combination of investor psychology and market cycles. How bull markets progress over time, pull in new investors, change in character and valuation over the course of each secular cycle is an important but oft overlooked point.

I define a bull market as an extended period of time, typically lasting a decade or longer, driven by broad economic gains which create an environment conducive to rising corporate revenue and earnings. Often, it is dominated by the rise or expansion of broad trends and new industries. The most dominant feature is the increasing willingness of investors to pay more and more for each dollar of earnings.

Consider the 1982-2000 secular bull market. Price-to-earning ratios on the S&P 500 began that cycle at 7 and finished at 32. Over that nearly two decade bull run, markets saw about a 1000% gain. Three quarters of the gains were due to multiple expansion. From a valuation perspective, stocks were cheap at the beginning, passed fair value somewhere in the middle of the cycle, and were expensive over the last 4 years at the end. Hence, valuation measures were not much help to investors over most of that period

Why is this significant? Because stocks begin the cycle cheap, end the cycle dear, and when the cycle ends, they tend to give back 30-50% of those gains. The challenging part from an investors perspective is that those losses will be made up through both dividends and price appreciation while the news is almost all bad. When the next secular bull market begins, those same investors who sold (or refused to buy) high P/E expensive stock markets tend to get caught up in all of the negative news flows. We have seen this too many times to count: Investor psychology leads the overly value conscious to miss the end of one bull market but even more importantly, then miss the beginning of the next cycle. Your comments as to why timing is doomed to fail are very well noted.

To quote the great Bill Miller, “Volatility is the price investors pay for performance.” To capture that upside, you have to be willing to modify how much valuation affects your investment making decision.

~~~

NK: Valuations weren’t helpful to investors darting in and out of stocks from 1982 to 2000 because they never are for that purpose. But they were a useful guide to future returns. The correlation between the S&P 500’s earnings yield and subsequent 10-year total real return was strongly positive during the period (0.67).

Your point about investor psychology reminds me of another reason valuations are useful: They’re the best gauge of the market’s mood. I often hear people arguing about whether investors are bullish or bearish about so-and-so stock market. No need to squabble; that information is in the valuations.

For example, the P/E ratio of the S&P 500 based on analysts’ forward earnings estimates is 25.4 as of Monday, according to Bloomberg data going back to 1990. That’s just shy of the record of 27 set in December 1998. So despite what anyone may say to the contrary, investors in U.S. stocks as a whole are demonstrably bullish.

More generally, valuations are among the best tools we have for gauging future returns, which has many important applications such as planning and portfolio construction. It’s a shame that their misuse by some has obscured their utility.

~~~

I originally published this at Bloomberg, July 9, 2020. All of my Bloomberg columns can be found here and here.