To hear an audio spoken word version of this post, click here.

Maybe it is a coincidence. Or maybe there are only so many storylines that can be told. As recounted by Joseph Campbell, the archetypical hero’s journey – shared by all of the world’s classic mythologies – are just variations of the same basic premise.

As a consumer of news and entertainment, I cannot help but notice the similarity between various storylines that seem to get told again and again. It is especially true in the world of finance, where the combination of vast sums of money and basic human emotions lead to the same plots repeating.

After skimming my personal library and Amazon purchase history and various Netflix/Amazon Prime/HBO views, a pattern has become visible. We can see similar themes, ideas, plots, and narratives all told again and again.

Here are the four intriguing thematic plots that seem to show up the most in finance:

1. Greed Blinded by Arrogance: The classic of financial literatures, featuring a bevy of fascinating players. The plotline typically looks like this: Some insight is found, one that allows a small fortune to be made. But for reasons of human avarice and excess, it is not enough. Forcing scale and leverage onto what began as a modest business perception leads to assuming much more risk, usually via leverage aka borrowed money. It was ends the same: eventually disaster strikes, fortunes are lost, it all ends in tears.

It works because this plotline is a literary mainstay: the rise and file and eventual denouement for all involved.

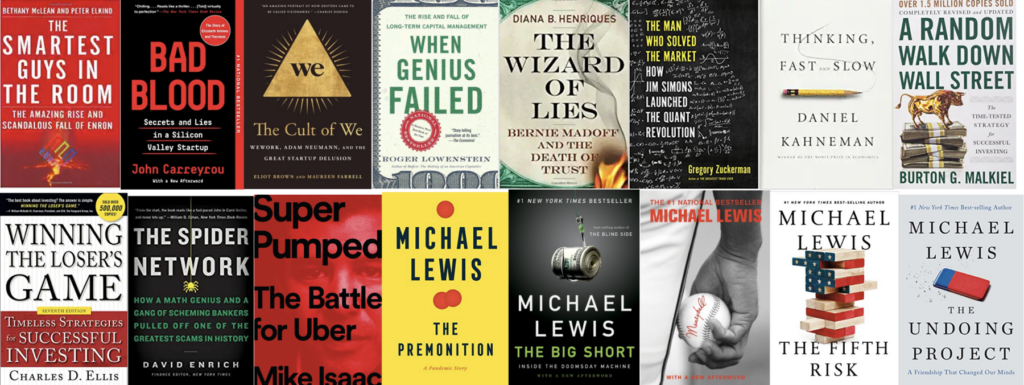

Three favorite examples: The genre classic is “When Genius Failed: The Rise and Fall of Long-Term Capital Management” by Roger Lowenstein. A newer version is “Super Pumped: The Battle for Uber,” by Mike Isaac – and the latest wonderful example is “The Cult of We: WeWork, Adam Neumann, and the Great Startup Delusion,” by Eliot Brown and Maureen Farrell.

2. Everything you believe is wrong: This is a broad category that includes tales of outrageous success, as well as academic literature that turned the existing explanatory econometric models upside down. It includes the fields of Behavioral Finance, as well as the Contrarians who altered our perception of finance.

A few academic examples include “A Random Walk Down Wall Street” by Burton G. Malkiel and “Winning the Loser’s Game” by Charles D. Ellis. Each of these changed people’s perceptions of how markets actually functioned. Malkiel’s insight went beyond mere market efficiency – he specifically detailed just how difficult it is to beat the market. He made the case for indexing as well as anyone since Jack Bogle. Ellis’ great insight was that for most investors, making unforced errors mattered far more than the occasional perfect slam shot. It turned investors’ perspectives upside down.

If a real world example interests you, see “The Man Who Solved the Market: How Jim Simons Launched the Quant Revolution.” by Gregory Zuckerman. From 1988 to 2018, Simons’ Medallion fund returned 66.1% annually before fees.

The list of Behavioral Economics plot archetypes is too long to list here, but these four stand out: “Thinking, Fast and Slow,” by Daniel Kahneman is pretty much the first and last word in the space from half of the duo who invented it. “Misbehaving: The Making of Behavioral Economics,” by Richard H. Thaler maps out how the entire field developed, including Thaler’s own notable contributions. “Predictably Irrational” by Dan Ariely is an accessible way to understand just how little rationality people have. Last, “Your Money and Your Brain” by Jason Zweig combines BeFi with actual investing advice.

3. Greed leading to Fraud: What happens when arrogance spills over to criminality? You get another sub-genre, quite distinct from our first set of examples. If we had to create a formula for this, it would look something like this:

Greed + Sociopathy = Felonies

The classic of this genre is Bethany McLean’s book on Enron: “The Smartest Guys in the Room.” So much bad motivations leading to so many crimes, with insider trading the least of it.

The fraud that shocked everyone for its sheer size and longevity was the Madoff Ponzi scheme. “The Wizard of Lies: Bernie Madoff and the Death of Trust” by Diana B. Henriques tells the $60 billion dollar tale of endless ego and avarice.

With Elizabeth Holmes trial just getting underway, the book to read is two-time Pulitzer-prize winner John Carreyrou’s “Bad Blood: Secrets and Lies in a Silicon Valley Startup.”

An overlooked book in this space I really enjoyed was on LIBOR: “The Spider Network: How a Math Genius and a Gang of Scheming Bankers Pulled Off One of the Greatest Scams in History” by David Enrich.

Lots of films worth seeing are in this same genre: Boiler Room, and Wolf of Wall Street (skip the book) along with Oliver Stone’s 1987 film, Wall Street.

4. Michael Lewis books: Only one author gets his own category, and that is Michael Lewis, the poet laureate of American finance.

The archetypical Lewis book1 begins with an enormous and important institution that is oblivious to oncoming trouble. Perhaps it is because it has calcified into an entrenched place in society; maybe it has a series of misplaced incentives. Regardless, it begins to fail over time – sometimes the cracks show up relatively quickly, other times, it is decades in the making.

As the entrenched power fails to see the forest for the trees, a scrappy band of quirky outsiders, invariably a group of intelligent misfits, see the oncoming train early. Their warnings always universally go unheeded. Disaster eventually strikes; Fortunes are made and lost; Lives ruined. Occasionally, catastrophe is averted but most of the time, not so much. Very often, the book becomes a movie.

See The Big Short/Moneyball/Blind Side/The Undoing Project/Fifth Risk/Premonition/

There are surely other plotlines that can be described as classic financial genres: Naiveté leads to problems is one; the Horatio Alger story is another.

But with Summer soon ending, I know some of you are looking for some new reading material. This is a great list to find some new books for Autumn.

_____________

1. With all due respect to Malcolm Gladwell, no, Lewis’ books are not biblical allegories.

click for audio