What My Worst Trades Taught Me About Investing

Losing money on Wall Street can be profitable in the long run.

Bloomberg, September 4, 2021.

To hear an audio spoken word version of this post, click here.

In a recent appearance on Bloomberg TV, anchor Tom Keene surprised me with this question: “What is your best Apple story?” I said that in the early 2000s I managed to snag a pre-release loaner iPod. It was obviously a new, digital version of the ubiquitous 1980s Sony Walkman. At the time, Apple Inc.’s shares were trading at $15, with $13 a share in cash on the balance sheet. I did not see a lot of risk in the shares. I pitched it to my firm’s 800 or so brokers, many of whom bought lots of shares for their clients.

But I was surprised when soon after the shares shot up to $20, the brokers began to sell. “Up big, 33%, gotta ring the bell,” is what I was told. I held on, and finally sold when my “stop loss” order was triggered on a pullback after the shares reached $45, leaving me with a 300% gain. “A triple!” I smugly declared, in what was probably the worst sale I ever made.

In a career filled with other bad trades, missed opportunities and judgment errors, some decisions stand out, not just for the lost money, but for the lessons learned. Here are four examples:

Apple at $15: I may have paid $15 a share, but that was numerous splits ago, which means that had I held onto that Apple stock through last year, my post-split cost basis would have been 26.78 cents per share. That was about $2.4 trillion dollars in Apple’s market capitalization ago. From this I learned two lessons: The first and obvious one was to avoid too tight stop losses. I was raising my stop with each $10 gain; a $13 stop on a $15 purchase became $23 once the price crossed $25. Volatility guaranteed that such a tight stop would eventually get executed.

But the more important lesson was on how to think long term. I was behaving like the (former) trader I was, and not the investor I had become. Trade management is important, but mine did not properly align with my time horizon or risk tolerances. They (eventually) fell into sync, but it – expensively – took time.

Robinhood’s 2015 seed round: “That is the dumbest investment idea I have ever heard.” That was what I told Howard Lindzon, who runs a small, successful venture fund and has been an early investor in too many tech winners to list (Facebook, Twitter, etc.). We were sitting outside the Ferry Building in San Francisco and Howard was pitching me on putting money into the seed round of Robinhood Markets Inc., a new app that allowed people to trade stocks for free. 1

“Howard, the world is moving from active to passive, from stock trading to ETFs. Why in the world do I want to own an app that gives trades away for free to young people with no capital? How are they ever going to generate revenue, let alone profits?” I smugly asked.

My weak defense: Robinhood was totally “off brand” from how we were investing at my firm and what I was writing for Bloomberg Opinion. And, Robinhood’s current success is (arguably) due to bored millennials looking for something to do during the pandemic lockdowns.

Still, it would have been a fantastic hedge, and the returns from the seed round have been nothing short of eye-popping. I recently told Howard, “Wow, I really suck!”

I learned several things. 1) Stay in your lane. My expertise was not in the venture space, so I should have deferred to the pro. 2) Beware of recency bias. An earlier startup Howard and I invested in never found an exit. That “sample set of one” colored my view. 3) Do not assume that any start up, or even mature company, will look the same in six months, let alone five years later. Failing to recognize these truisms meant that I left a lot of money on the table.

Behavioral insight: When I was pitching Apple to retail brokers to buy for clients, I could not help but notice the certainty of some people’s conclusions about the company’s attempted turnaround. Even my mother, a former real estate agent and stock dabbler, sounded like everyone else when she said to me: “Apple? They are going out of business!” (Note my own smugness in the above examples.)

I have taught myself to pay attention to any trading idea where my knee-jerk reaction is disgust. The reason is because that reaction likely reflects all of the bad news that is likely already priced in, not the good news that may come. The lesson to be learned is in recognizing your emotional reaction as revealing a widespread, and potentially wrong, sentiment.

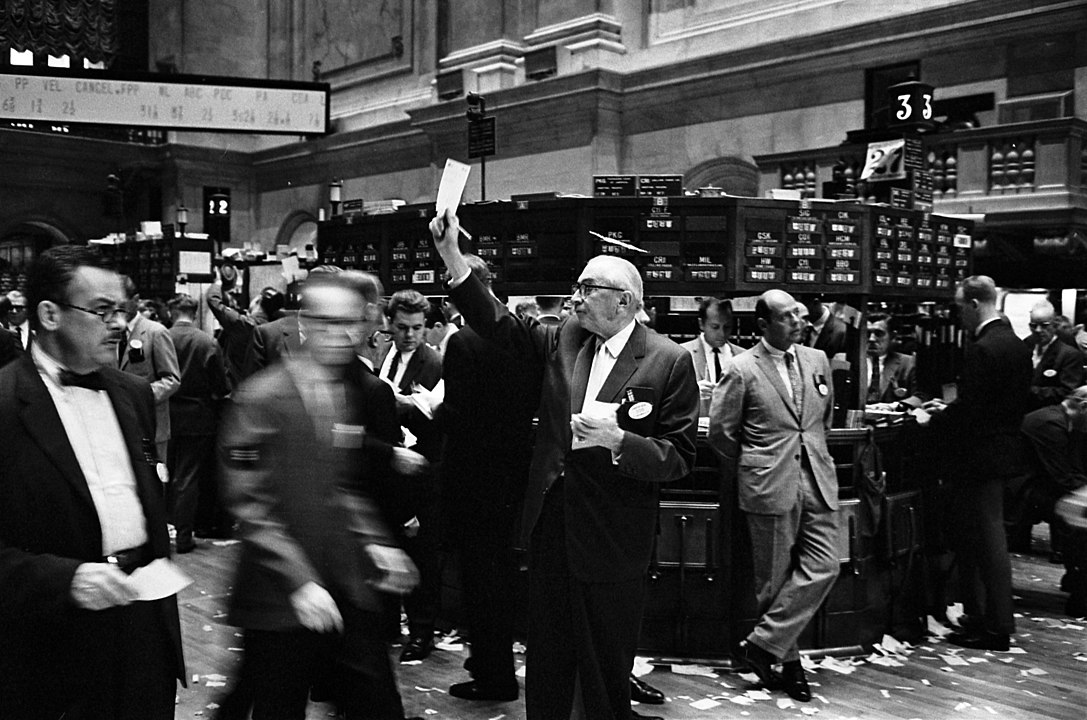

Short the market: Short-sellers have become an endangered species on Wall Street, and that is too bad. The firm I worked for had a number of shorts heading into 2008: American International Group Inc., Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. and CIT Group Inc. Before those, there was Bear Stearns Cos.2

But even getting those trades rights turned out to be missed opportunities. First, there was a constant threat of a “short squeeze” and our positions would be called away at any moment. Second, we did not size the positions correctly. The gains from these positions failed to offset the losses (in dollar, not percentage terms) of another portfolio manager had that were money-losing long positions. These shorts were “high-conviction” trades, and we should have had much more of each.3

Last, and most important, was the limited upside. Short sellers can only double their money – make a 100% return – if a stock goes to zero. I lamented the modest returns of what looked like great trades to Seabreeze Partners’ Doug Kass, who made this simple suggestion: Marry a put to your short positions. 4 Its painfully obvious in hindsight, but it was how Doug traded from the short side. I have not had any high conviction shorts since then, but next time, I would marry a 20% put position to any equity short.

The lesson is that you must have the courage of your conviction. If you really believe in a trade, it should be meaningful enough to affect your profits. Otherwise, why bother?

I shared my Apple experience on Twitter and was rewarded with wonderful examples of terrible trades. There always seems to be much more to learn from our failures than our successes. Which leads me to this simple question: What was your worst trade? Hit me up at BRitholtz3@Bloomberg.net, and I will share the best worst trade stories in a future column.

UPDATE: September 7, 2021

Since this was published, a few people have shared some of their worst trades, including JC Parets, Banyan Hill, and others.

________

1. Howard recalls this as 2014, and he may be right.

2. See this discussion on how one of the partners managed to snatch defeat from the jaws of victory…

3. Note this is not hindsight bias, but actual arguments made in real-time. A classic problem with managing a portfolio by committee instead of single manager.

4. Meaning, for each $100 of equity shorted, include $20 of put options (shorting that much less common).