Physics has been seeking a grand “Unified Field Theory” that can explain everything in the universe. I sometimes wonder if we can find a similar overarching theory covering bad decision-making. The closest I have found as a single point of failure is the Dunning Kruger effect.

Recall last week, we were thinking about the impact of retiring Baby Boomers on the equity markets and of rising rates on housing. Rereading that this morning, I realized I buried the most important part of the discussion:

“Both questions are a fascinating reveal of how a common understanding of complex subjects barely scratches the surface of the rich complexities that lay beneath. All too often, the superficial narrative fails to capture the reality beneath.”

The discussion was really about how the “conventional wisdom” is often only a superficial read, and how initial appearances can be misleading due to complexity we may not be aware of. Rates are obviously important to housing, but we must also recognize that they are far from the sole driver of the residential real estate market. Many other factors can be as or even more important.

Our own lack of depth in a specific skillset is why we miss that complex reality. As a species, our tendency is towards combining a little bit of knowledge with some overconfidence. This combination easily leads to fundamental misunderstandings.

Can this one-two punch explain why it is so easy to get so much wrong in the capital markets so often?

Let’s consider another question, this one on U.S. equity valuations:

“Baby-boomers’ huge flow of 401K plan contributions helped to drive equities higher; now that ~70 million Boomers are retiring, when do demographics flip this from a huge positive to a net drag?”

The demographic question touches on a big issue: $6 trillion dollars in 650,000 (401k) retirement plans held by tens of millions of Americans. The initial assumption is the retiring boomers matter a great deal, but a deeper dive into the structure of equity ownership suggests that it probably does not.

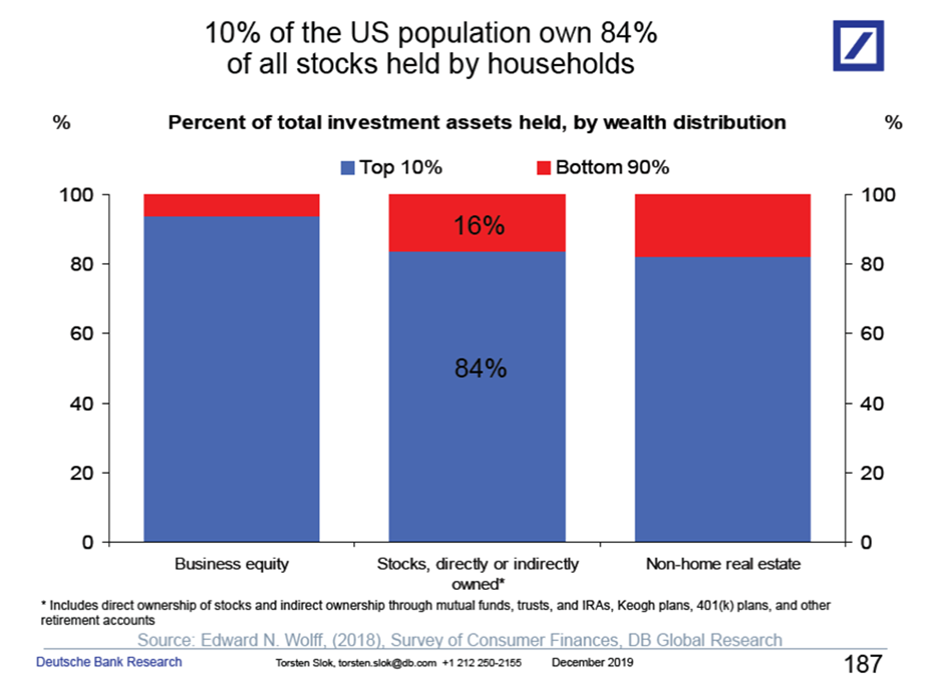

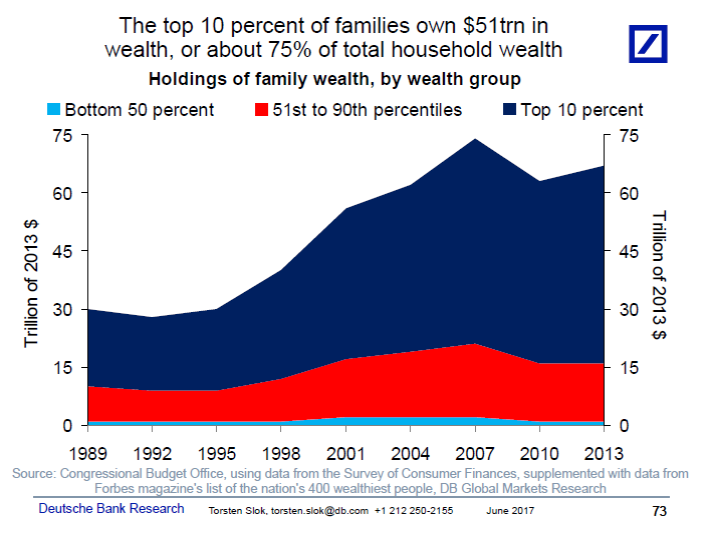

I suspect most of us have a distorted viewpoint of the average investor versus the total capital in the market. As the charts above and below show, the vast majority of equities are held by the top 1% and 10%. This demographic cohort is simply not a net seller due to impending retirement because the tax consequences would be too great. My experience is this group takes a comprehensive approach to managing generational wealth transfer, philanthropy, trusts, etc. so that their assets move with as little capital gains tax paid as possible.

Note that the vast majority of stock held by individuals — the top ~10% of stock owners who control ~75% of all equities — is likely to manage their assets this way.

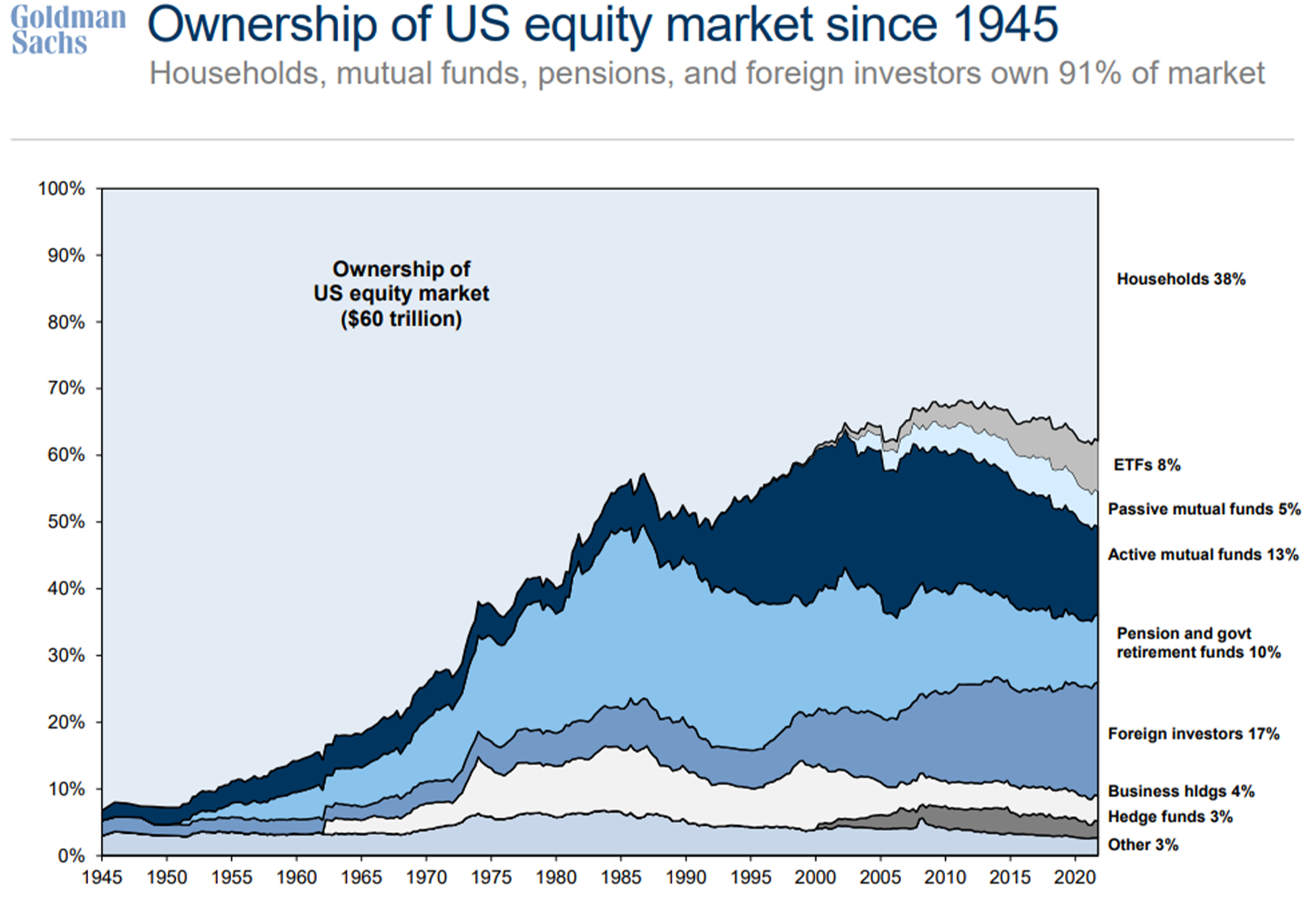

Adding a layer of complexity, at one point in time, all of these stocks were owned directly by individuals as specific company stock. As Ben pointed out via his favorite chart at top, ownership of U.S. equity market since 1945 has shifted dramatically to different investment vehicles. U.S. households once owned 95% of all stocks individually in brokerage accounts; today, ownership is is via ETFs, mutual funds, pensions, hedge funds, foreign investors, etc.

Estate taxes are why appreciated equity is transferred this way. These scenarios do not usually involve much stock selling. But as we have seen, most people have little idea about exactly how top-heavy equity ownership is. The market is far bigger, more professional, and much more institutionalized than most people realize.

~~~

Unrelated story: A few years ago, a friend came out with a fantastic idea for an Index and ETF; even better, he managed to snag an amazing stock symbol. (I am purposefully omitting the specifics and the names of the fund managers, sponsors, banks, etc.) It had an ESG twist, and so was a potential fit for foundations, endowments, family offices, etc. He put together a great board of advisors, a clever idea for adjusting the index — it was all so brilliant. The index even outperformed its S&P500 benchmark all 5 years running.

Despite all of those great elements, it gained no traction. Even the outperformance and the hot sector it was in failed to attract much institutional capital. Five years later, despite the idea and ticker still being great (at least in my mind) the fund shut down due to lack of interest.

I asked my buddy if he had any interest in selling the stub (assets include name, intellectual property, board, ticker symbol, etc.) for pennies on the dollar. I still like the idea, and imagine how easy it would be to turn it into a giant success, a billion dollar ETF winner.

Before putting any time or capital at risk, I wanted to discuss it with an expert. In my circles, nobody knows more about the ETF industry than Dave Nadig. We looked at the idea and who the potential ETF/index buyers might be. We kicked around how the target demographic makes these decisions, how they check which box, who they consult with, what other parties advise the decision-makers. Last, we considered why other like-minded funds similarly failed to attract much capital.

Our key conclusion? Despite the sexy idea and stock ticker and great performance — and my enthusiasm — it was only a so-so investing vehicle, unlikely to attract much capital. Endowments, Foundations, and other big institutional buyers would rather create their own stock screen and buy the positions themselves than outsource that to a third party that pre-packaged it into an ETF.

Hence, I saved a lot of time and work and headache and capital, simply due to my awareness of my own astonishing ignorance. I don’t usually think of humility as my strong suit, but I would chalk this one up to a mix of concern, fear and recognition of my lack of competency in this space.

I consider that a giant win…

~~~

Danny Kahneman has suggested that simply knowing about cognitive biases does not help in the fight against succumbing to their effects. I never want to be on the opposite side of an intellectual argument with Kahneman; however, I take hope that some of the more egregious errors can be avoided. When we look for disconfirming evidence, we can avoid some aspects of confirmation bias. Similarly, instead of thinking about things in terms of what we do know, perhaps it might be more useful to consider thinking more in terms of what we might not know. Hey, perhaps we can even make better decisions this way.

Humility is deeply undervalued on Wall Street.

Previously:

What If EVERYTHING Is Narrative? (June 21, 2021)

What If Everything is Survivorship Bias? (aka The Hidden World of Failure) (October 23, 2020)

Stock Ownership:

Distribution of Household Wealth in the U.S. since 1989 (March 10, 2020)

Stock Ownership in the USA (January 14, 2020)

Wealth Distribution Analysis (July 18, 2019)

Composition of Wealth Differs: Middle Class to the Top 1% (June 5, 2019)

Wealth Distribution in America (April 11, 2019)

US Wealth Distribution, Stock Ownership Edition (June 30, 2017)