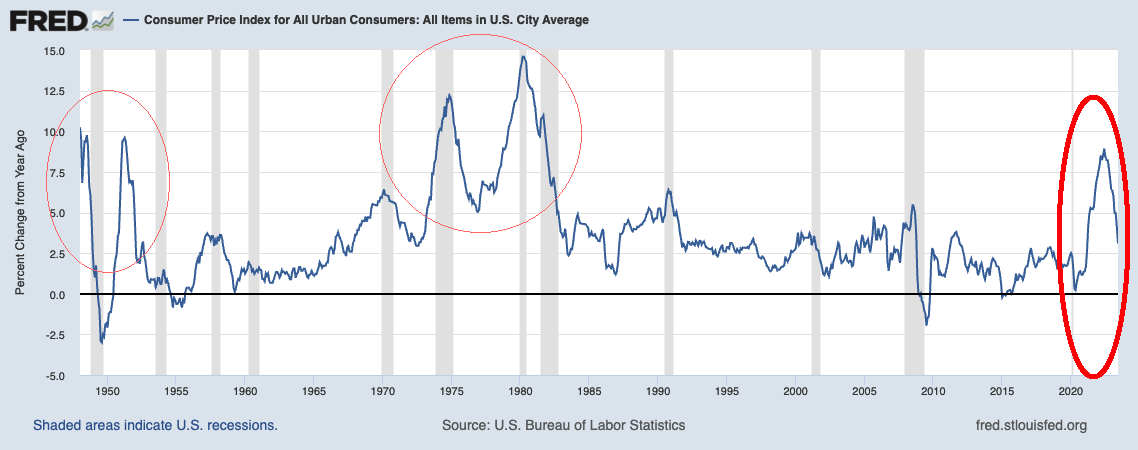

BLS reported the Consumer Price Index was up 3% year over year in June. It has been a near round trip from the prior decade’s range of 0-2% up to the 9% peak, and now back down to 3%, as the FRED chart above shows.

Over the past year, I have been writing a lot about inflation — what people get wrong about it, why the FOMC is usually late to the party, and what the various causes of inflation (real, modeled, and imagined) actually are.

All of this research into the space has led me to have ideas about inflation, many of which are out of step with the mainstream. Here are 12 ideas that are (or were) contrarian thoughts on inflation.

1. Inflation peaked June 2022; After making new highs a year ago, it has been falling rapidly ever since.

I have been posting on this since June 2022. This was a contrarian position for most of the period since, but after the May and June CPI reports, this idea is finally moving into the mainstream (Traders had figured it out sometime around October 2022).

2. “Long and Variable Lags?:” The FOMC rate increases and other Fed policy actions are all felt in the broader economy eventually. Exactly how long it takes is the subject of debate. Economists who came of age in the 1970s/80s all seem to be wed to an outmoded model.

In the 1970s, when inflation was persistent and home mortgages were double digits, it was fair to assume it may have taken as long as 18 months for FOMC policy to be felt. Especially considering how opaque the Fed was back when they didn’t even tell you when they raised or lowered rates — you would figure it out from the bond market! Prior to 1994, the central bank did not put out a policy statement or hold a press conference.

But today? That 18 months sure seems long.

The modern economy runs on credit, and the Fed has been transparent, telling the market exactly what going it’s going to do. It should result in a much shorter lag between Fed action and reaction in the economy.

3. Is Labor Inflationary or Deflationary?: The biggest factor in wages has been a shortage of workers across numerous industries; what is needed is more workers. I am at a loss to see how higher rates make that happen.

Wages at the bottom half of the economy have lagged most important metrics (Productivity, CPI, Corporate earnings, etc.) over the past 3 decades; they were a deflationary factor in the economy. But the widespread US labor shortage has led to even the lowest-paid workers getting raises, which the FOMC believes is inflationary.

Economists like Lawrence Summers are stuck in a 1970s mindset. His claim that the only way to end inflation was to throw 5 million people out of work was not just wrong, it relied on an embarrassingly outdated model (it was also unnecessarily cruel). It’s a good thing so few listened to him; it’s a better thing he isn’t the Fed chairman — the resulting recession would have been disastrous.

4. Transitory wasn’t wrong, it just took longer than expected.

A once-in-a-century pandemic with an unprecedented global lockdown simply took much longer to unwind than expected. There was literally no modern analog or comparison, and everyone was forced to just make a guess.

That said, 27 months instead of 12-18 is less of a miss than many have made it out to be.

5. Inflation Models are Inaccurate. PCE, CPI, and just about every inflation model I track is flawed but useful. Those that are consistent can be used as a baseline for historical analysis. However, relying on them to make real-time policy decisions is deeply problematic.

They are lagging, they make assumptions that can lead to skewed results, and they assume the world is less complex than it really is. They rely on historical data, which can lead (as it did in the current situation) to faltering results as novel situations arise.

Any organization that fails to understand this is at risk of making substantial decision-making and policy errors.

6. Inflation Expectation Surveys are Foolish: They are wrong. And dumb. And pretty much useless. Stop relying on them…

7. The Fed is Driving Home Prices Higher: Three factors have reduced single-family home supply, thereby driving real estate inflation:

A) Big post-GFC decrease in new home construction;

B) Pandemic home purchases without a corresponding sell,

C) 61% 0f outstanding mortgages have an interest rate of less 4.0%. Those low rates lock in homeowners who cannot afford to pay 7.5%+ for a new mortgage on another home.

All of this adds up to a huge shortfall in the supply of homes available for sale. We can’t change what builders did from 2007-2020, nor can we alter the behavior of buyers in 2020-22, But we are locking in potential sellers because of higher (too high) mortgages. Higher rates only make this situation worse.

8. The Fed is driving OER higher: Given the shortage of housing, the rapid increase in rates has perversely caused more, not less inflation. At least, in the Owner’s Equivalent Rent (OER) portion of CPI.

I have been railing against OER for nearly two decades; hopefully, this part of BLS model will get updated soon.

Note: In the mid-2000s, an era of plentiful houses and easy credit, OER perversely drove CPI lower and made CPI inflation look milder than it really was…

9. For lower inflation, lower rates: The main drivers of current inflation NOW are apartment rental costs, shortage of homes, and too few workers. Raising rates won’t fix these issues and arguably, make them worse.

FOMC raising rates from these levels not only makes OER look worse, it reduces single-family home supply, makes houses more expensive, but also sends more people into the rental market — making apartment rentals higher.

10. Consumers AND Companies were inflation drivers: Yes, consumers suffer from inflation, but when they willingly pay up for goods and services regardless of price increases they cause inflation. This is true for necessities (food, energy, clothes), in discretionary items (travel, 2nd homes), and most especially luxury goods (Watches, sports cars, bags, jewelry). Excess demand for goods during the pandemic led to goods inflation; excess demand for services post re-opened led to services inflation. Following each of those surges were somewhat different types of Inflation.

Companies took advantage of the chaos to push through higher prices when they could. I got this wrong initially but I eventually came around.

11. Lose the 2% Inflation Target: Seriously. After the GFC, the economy was sluggish and ZIRP/QE had driven rates near zero, 2% was a reasonable upside target. But after $5 or 6 trillion in fiscal stimulus, and mortgage rates at 7.5%, perhaps 3% — even 2.5% — makes much more sense as a downside inflation target.

12. The Fed has already won: Mission accomplished! Jerome Powell can take the summer off, enjoy fishing at Jackson Hole, and really, just chill out for the rest of the year. There is no need for further increases in rate as the battle is already won.

~~~

To be fair, the Fed was late to get off zero, late to recognize inflation, late to act, and they are now late to recognize inflation has fallen radically. Still, even a blind squirrel finds a nut now and then, and they should take the win and stop here.

They are at risk of snatching defeat from the jaws of victory…

Previously:

Inflation Expectations Are Useless (May 17, 2023)

What the Fed Gets Wrong (December 16, 2022)

What’s Driving Inflation: Labor or Capital? (November 7, 2022)

How the Fed Causes (Model) Inflation (October 25, 2022)

Why Is the Fed Always Late to the Party? (October 7, 2022)

Transitory Is Taking Longer than Expected (February 10, 2022)

Who Is to Blame for Inflation, 1-15 (June 28, 2022)

Deflation, Punctuated by Spasms of Inflation (June 11, 2021)

What Models Don’t Know (May 6, 2020)

Confessions of an Inflation Truther (July 21, 2014)