Yesterday, I had a very interesting discussion with Aaron Brown. We discussed some issues with his column “401(k) Plans No Longer Make Much Sense for Savers.” Here is his base premise:

The tax advantage of a 401(k) depends on four factors, all of which have changed dramatically since 1980 to the detriment of 401(k)s. For a median-income married couple with two children:

- The marginal federal income tax rate was 43% in 1980, 12% today

- The capital gains tax rate was 28% in 1980, 0% today (FN1)

- The likely retirement bracket tax rate was 15% in 1980, 12% today

- Interest rates in 1980 were around 15%, compared to 0% today

I generally disagreed with the take, but not for the reasons you might suspect. It was due to bullet point 2, which is explained in a footnote:

“Median-income, four-member households in retirement paid 0% capital gains taxes in 2018, the last year for which data are available. Higher-income households and those in different tax situations may pay at rates of 15% or 20% on long-term capital gains.”

I can’t swear this head of household had zero capital gains, but its likely damned close. Hence, the framing here is not just an outlier, but a unicorn.

He is not the typical 401k contributor. Hell, 401k? The odds are that this American is broke, has little to no savings, is worried about paying for college for his two kids, and wants to buy a house in a good school district (but cannot afford to). The very last thing on his mind is his retirement in 35-40 years.

My views are colored by pragmatic, real world experience. What percentage of 410k accounts and assets are held by people who are similar to this hypothetical: A 30-year-old head of household with a stay-home spouse and two kids, earning $50,000, with a no match employer?

Very, very few.

Which leads to this: Lots of people in our industry like to assume investing has been “Democratized,” and while we all wish it were so, it is a misguided, overly optimistic perspective.

I looked at the distribution of wealth via a new Federal Reserve data series analyzing the “comprehensive measure of household wealth” last year1, titled Wealth Distribution Analysis (Bloomberg). The numbers are pretty shocking: “The top decile of America holds almost about 70% of the national wealth — 31% is held by the top 1%, while the rest of the top 10% holds about 39%.” This covers stocks, bonds, private assets and real estate.

That stat is so astonishing, I feel compelled to repeat it, in bigger, bolder print:

70% of all wealth in America is held by 10% of the population.

That’s just assets, what about the flip side of this — debts?

Not only does the Bottom half of earners own little to no stocks (or other assets), they also hold most of the debt. So as to the question of plausible return and future tax assumptions for our head of household: He looks to be totally screwed. He is too broke to max out his IRA, let alone worry about a 401(k).

But — and here is the thing — he is not the main user of 401(k)s. That would be an upper middle class, likely a 2 income family, making $150k+ — probably more, depending upon where they live. What a 30-year-old head of household with a stay-home spouse and two kids needs is: A good job, regular salary increases, medical insurance, and more than a little bit of luck. 401(k)s are the least of his problems. (And I know all about the miracle of compounding)

My 401(k) began in the 2000s; My employees get a 4% match. RWM clients’ 401(k)s are about ~10% of assets but ~3% of revenues. They are mostly Vanguard funds, with management fees around 25 bps plus VG’s 5-7bps.

I won’t argue against those who claim 401(k)s benefit the wealthy or upper classes, because surely they do. Indeed, the stock market continues to benefit primarily the wealthy and the professional classes.

~~~

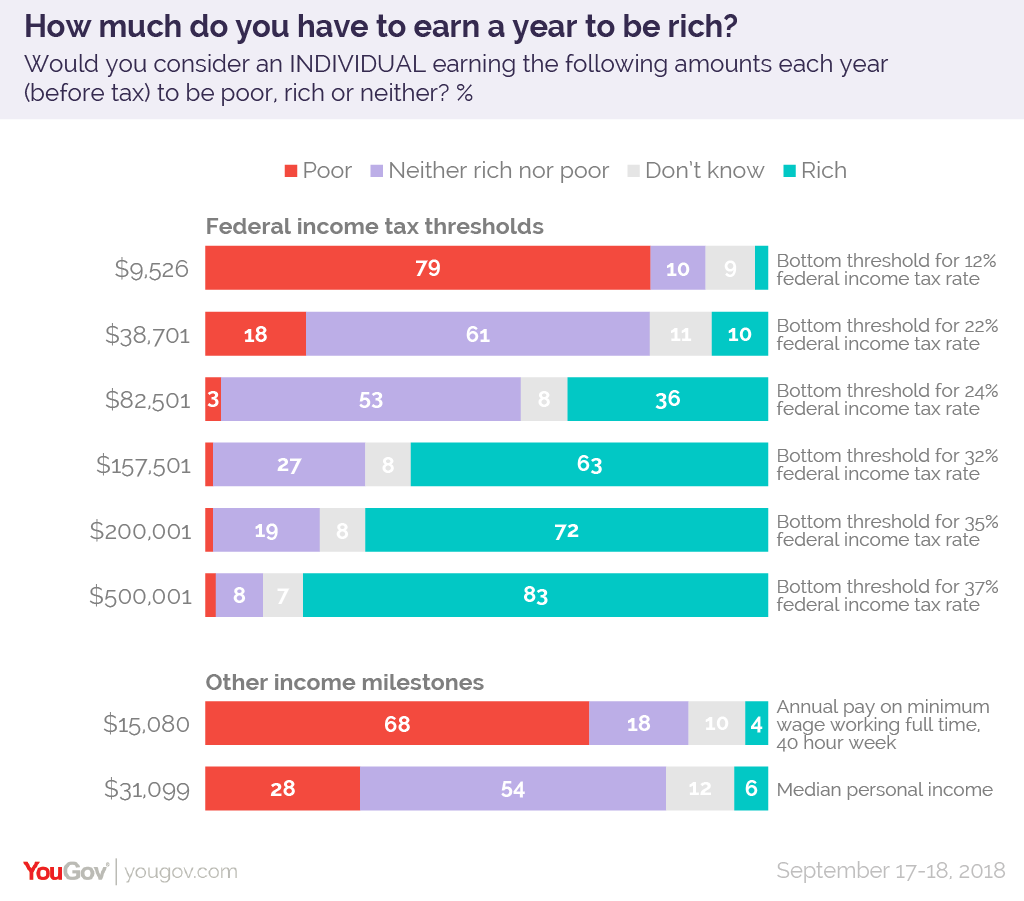

Some recent data came out looking at people’s attitudes towards how much money they think they need to have to be rich. As you might have noticed, its a topic I have been thinking about a lot lately. I hope to have more to say on this next week.

UPDATE: July 24, 2020

Bad advice on TikTok: Can financial advisors fight back? Dunning Kruger comes to TikTok to give you really bad financial advice

Previously:

Wealth Distribution Analysis (July 18, 2019)

Wealth Distribution in America (April 11, 2019)

Understanding Wealth Comparisons

_______

1. See pdf Distributional Financial Accounts of the United States

How much money do you need to earn a year to be considered rich? And how little must someone earn to be considered poor?

Source: YouGov