Source: JP Morgan Asset Management

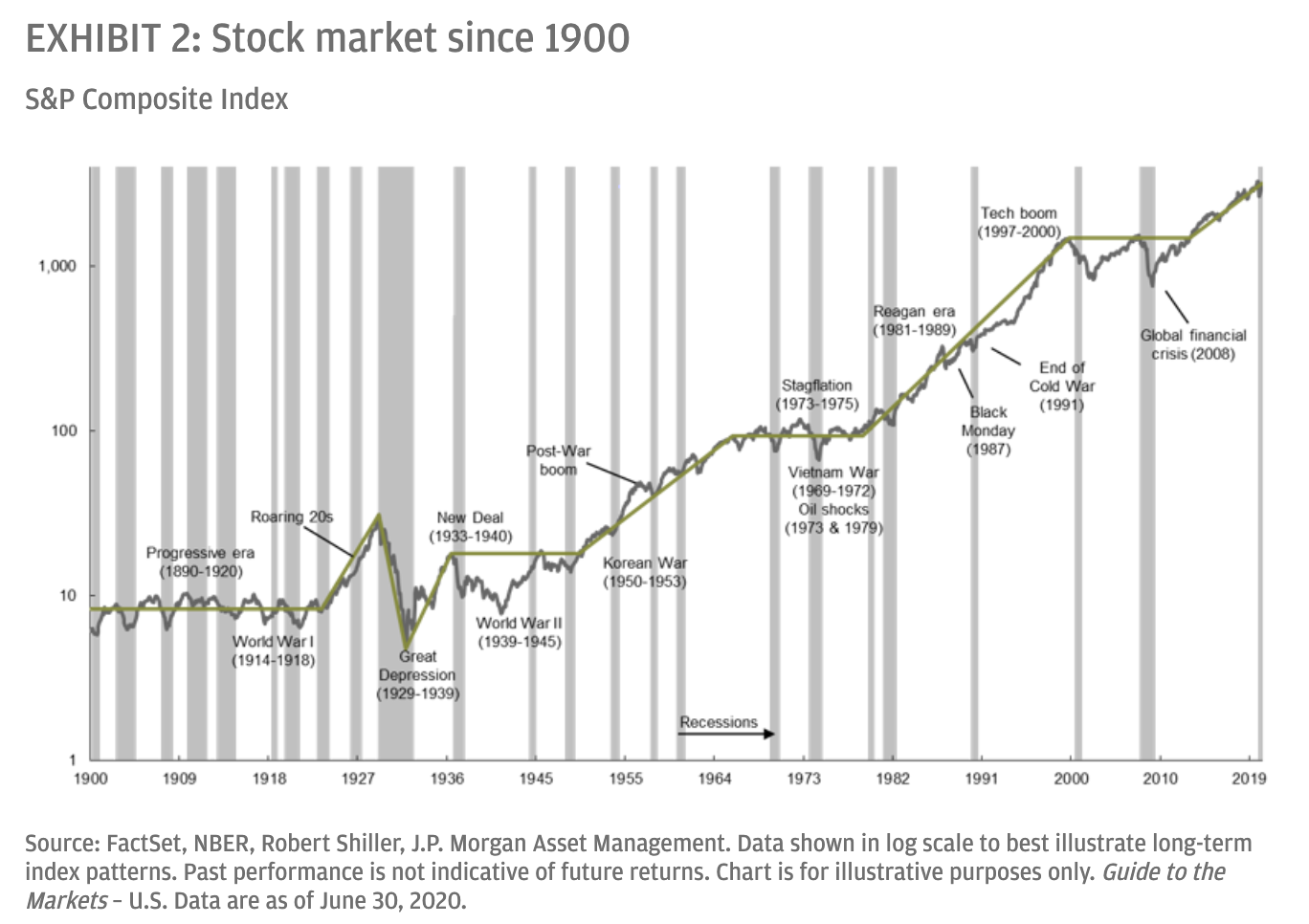

The above is one of my favorite charts.

This version comes from a JPM discussion on “Framing Bias.” It raises interesting issues about how decisions are influenced by the way information is presented:

“What level of returns should we expect from equity markets? The answer changes depending on the time period – when investors allow an incomplete picture to influence their decisions, it is an example of framing. While it appeared the market had climbed to untenable highs post-GFC, [but] if we take a slightly longer view, the overall market return was actually flat between 2000 and 2012. During that time period, the market had an average annual total return of 0.6% per year and a cumulative total return of 6.8% – effectively a sideways market.”

I draw a slightly different conclusion from the long term series of secular bull and bear markets. (Assuming you are not a trader), when you consider the chart above, investors are presented with several choices:

1. Time the market, moving in and out before long bear markets;

2. Buy & Hold, waiting out the decade (or longer) poor returns;

3. Reduce Risk, by making tactical moves to modestly shift asset class exposure.

The discussion of framing suggests there are other alternative contexts for these choices: For example, you can use tactical allocation shifts to manage behavior rather than to affect risk or returns.

Having now lived through two bear markets that were a decade+ long, I wanted to find a new way to think about what Buy & Hold investors should do during bear markets.1 To stick with the concept of framing, these investors should also pay attention to inflation, compounding, and how the idea of longer cycles negatively impacts our comprehension of valuation and prices.

A quick real estate story:

When we were purchasing our first suburban home in the late 1990s, we had narrowed it down to two houses. One was in Sea Cliff, a charming town on the North Shore of Long Island. The other was about 5 minutes south in Greenvale, in the Roslyn school district, which was a highly ranked (but became a notorious scandal-ridden) district.

Both homes cost about $250k. Sea Cliff was more quaint, but in front of that house was a bus stop. It was noisy, from inside you could hear the chuffing of the bus as it stopped, brakes squealing, diesel engine rumbling. I could not get past that, and so we ended up in Greenvale.

But the house I truly fell in love with was a Double Dutch Colonial in Sea Cliff. It was exorbitantly expensive at $400k. Now, if $250k and $400k don’t sound that far apart, you are being affected by your framing of current pricing. At the time, $400k — well over half again as expensive as our price range — was a giant gap far beyond what we could afford for a starter home.

I don’t see that house on Zillow, but a home next door (not as nice) is now up for sale at $1.795m.

That pricing reflects several real estate bull and bear markets, where prices advanced three steps, and then retreated one. But it also reflects how our comprehension of compounding and inflation creates valuations and prices that are difficult to grasp. Mortgage rates fell, suburbs became more attractive, and suddenly an asset appreciating 4X does not seem so wild. Around the same time (97?), the S&P 500 Index was about 800, and it is also 4X today.

One last thing: I have a very vivid recollection around this time of people taking a little off the table from appreciated equity and rolling that into real estate — trade up homes, vacation properties, etc.

Which makes me wonder about this: Maybe equity investors should think about bear markets — or even the last innings of bull markets — as opportunities for long-term accumulation phase with expected returns of zero or negative over the short term.

That sounds counter-intuitive. But given what we know about how unsuccessful investors are when it comes to market timing, what other choice do they have but to reframe the low return and/or expensive part so of the market cycle?

Buyers during the 1966-82 and the 2000-13 bear markets were essentially accumulating assets for the next bull market run. It surely felt awful to be a Buy & Hold stock accumulator in the 1970s, just as it did int he 2000s. But boy, did it pay off when the next bull cycle began.

I expect that when we look back at the end of this cycle (the 2013 – ?? bull market) and past the next bear cycle, if we might draw the same conclusion. Just an idea I am noodling around with.

~~~

More on this (eventually) . . .

______

1. I have done better than okay via market timing, but I keep coming back to Michael Mauboussin‘s question: Was it skill or luck? Not knowing for sure, I am willing to dabble with a little fun money but unwilling to risk real capital on trying to time in and out.