The reactions to the two most recent major economic crises provide a wonderful laboratory to do a compare and contrast between different types of rescue policies.

Consider if you will the government response to the great financial crisis (GFC) of 2008-09. To unfreeze credit markets and ensure there was sufficient liquidity for the system as a whole to keep operating, the Federal Reserve took rates to zero, set up a variety of facilities to ensure banks could stay open, focusing on the financial system as a whole but mostly ignoring the broader economy.

To their credit, the Federal Reserve avoided a catastrophe. The financial system managed to keep operating, corporations met their payrolls, and banks were able to perform their crucial service. This is no small thing – Ben Bernanke and the Federal Reserve deserve credit for successfully preventing an even bigger disaster from occurring.

But the costs for the way we avoided the financial abyss were consequential. Especially, when we consider how absent Congress was in terms of providing a substantial fiscal response to the crash of the entire economy.

Beyond the Federal Reserve unfreezing credit markets, there were two crucial results of their actions: First, the low cost of capital and borrowing helped corporate America increase its margins significantly. The next decade saw record revenues and profits leading to an epic bull market in U.S. equities. Annual average returns of 13% were far in excess of historical averages of 8%; equity owners saw a 700% gain over the next dozen or so years. Similarly, single-family homes and apartment buildings (real assets) saw a massive increase in value.

The key takeaway of this was that asset owners did well (and in many cases, exceedingly so).

But the second repercussion was more problematic: A mostly monetary stimulus left behind most of the American population. The top 10% of America owns 89% of the public traded equities; there are 82.51 million owner-occupied homes. This means that the Federal Reserve response benefited somewhere between the top ten and top 25% of Americans.

At the time many of us decried the lack of fiscal stimulus, but the deficit Hawks and partisan hacks one out. Congress did enact a modest fiscal stimulus of $787 billion. But a third of this was a temporary extension of tax cuts, and another third a temporary extension of unemployment benefits; this left a modest $200 billion as the fiscal stimulus, an amount that has proven to be laughably insufficient.

The result is a subpar recovery, best characterized as soft GDP weak job recovery poor retail sales, and very little wage gains.1

How do we know this? Because we have seen the results of the $4 trillion in 3 separate CARES Act fiscal stimulus in 2020 and 2021. The U.S. put $1.395 trillion in Unemployment Insurance into the hands of American families — about 5X what was done during the GFC. The result has been enormous gains by the bottom half of the country, especially entry-level and minimum wage workers. All of that cash in the hands of the average household was used to purchase goods to replace the services that were no longer available due to the pandemic.

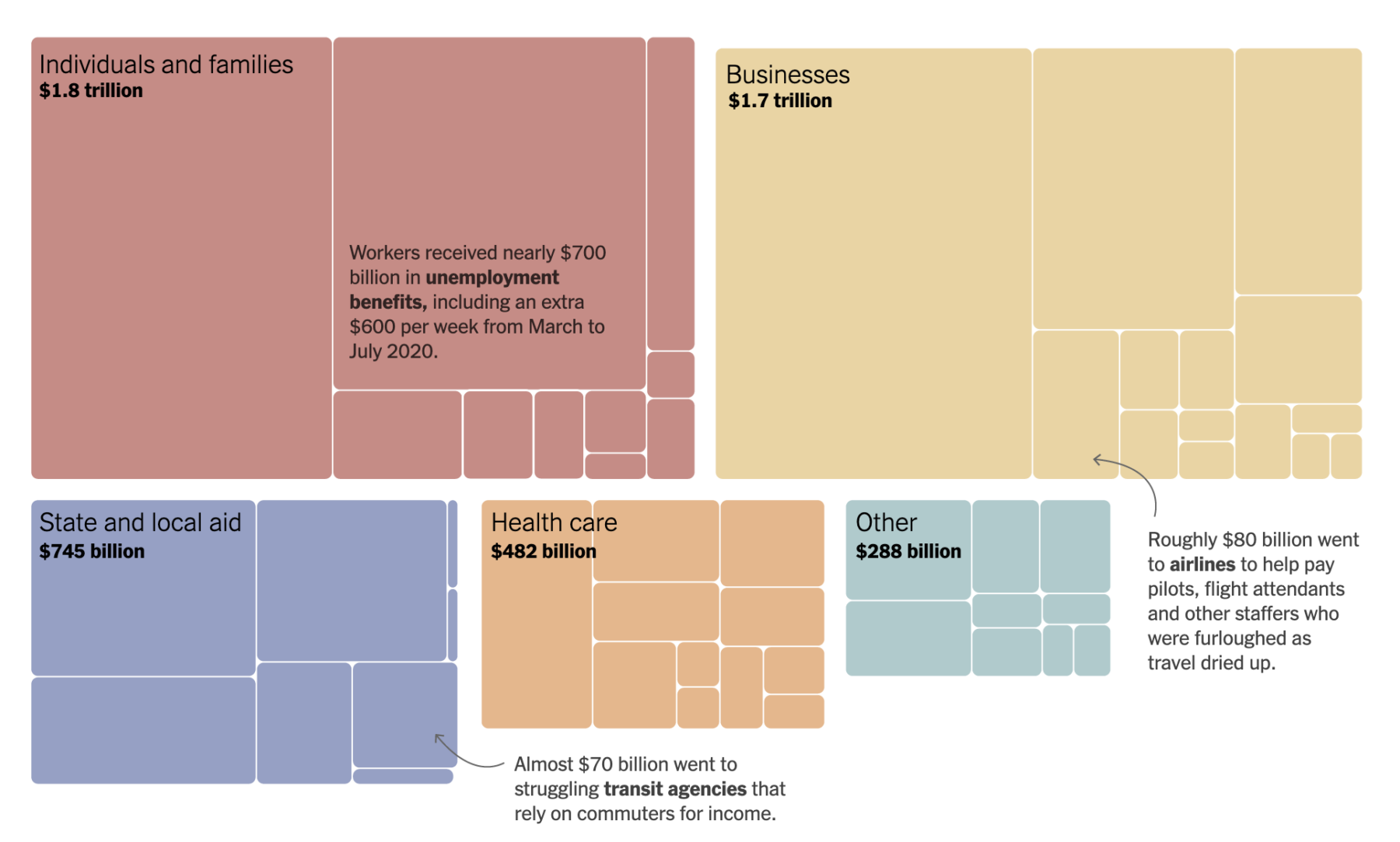

As the graphic at top shows, another $1.7 trillion in aid went to businesses in addition to the $1.8 trillion to households; states received $745 billion while healthcare was given $482 billion.

The net result?

Unemployment has fallen to 3.8%, retail sales are at all-time highs and the cash, in combination with supply chain tangles and semiconductor shortages—all caused by the lockdowns—have sent inflation back to 40-year highs. The Russian war against Ukraine is sending energy and food prices even higher.

None of this should come as a surprise. Ever since Lord Keynes wrote so eloquently on the subject, we know the result of fiscal stimulus as a substitute for household and business spending. We also know that austerity only makes economic downturns worse, and the time for balancing the budget is when the economy is doing well, not poorly. Countercyclical spending would have been far more useful in 2008-09 than the tax cuts we saw in 2017.

One of the most useful tools in the strategist’s toolbox is the counter-factual. Hypothesizing alternative realities had different decisions been made by policymakers at key points in history is a wonderful way to consider the ramifications of those decisions. (I have used this tool frequently and on occasion with great success).

Had we seen substantial fiscal stimulus in response to the Great Financial Crisis, the subsequent recovery would have been more robust jobs would have regained their pre-financial crisis levels much sooner, wages would not have lagged by as much as they did. Hopefully, policymakers keep this in mind the next time the country is confronted with a substantial economic crisis.

Previously:

Time to Stop Believing Deficit Bullshit (September 3, 2021)

$1.395 Trillion Peak Unemployment Insurance (March 4, 2022)

Shifting Balance of Power? (April 16, 2021)

Stimulus, More Stimulus and Taxes (January 25, 2021)

Go Big: The U.S. Needs Way More Than a Bailout to Recover From Covid-19 (April 30, 2020)

Unintended Consequences, Part III: The Great Financial Crisis (April 29, 2020)

Go Big (little version) (May 3, 2020)

All Hail the Counterfactual ! (November 12, 2018)

Why America Has a Two-Track Economy (September 27, 2018)

How Growth, Taxes & GFC Affects GDP (August 6, 2018)

Can We Please Have an Honest Debate About Tax Policy? (October 2, 2017)

Deficit Chicken Hawks vs Ronald Reagan (July 13, 2010)

_______

1. There is a credible debate to be had as to whether this weak recovery was done on purpose – partisan sabotage designed to recover the White House – but I will save that discussion for another date.