How far behind the curve is the FOMC?

I’m in the last month of book leave but I felt compelled to pop out at what feels like a seminal moment in the economic/market cycle to discuss how we got here and what the impending rate cuts might mean going forward.

Quick caveat: The world is always more complex and nuanced than we see in the media or academia; there are millions of little unknown details and our penchant for narrative fallacy leads to clean and compelling storylines that often lack verisimilitude.

Let’s start at 30,000 feet before zooming in on the details. Following the financial crisis, ZIPR/QE sent rates to 0%, fiscal stimulus was mostly non-existent,1 and so the 2010s post-GFC recovery decade was characterized by weak job creation, poor wage gains, soft consumer spending and modest GDP. Inflation was non-existent, and CASH was king.

Historically, this is what post-financial crises tend to look like – except for those periods where governments apply the fiscal stimulus lesson we learned from Lord Keynes to jump-start an economic expansion.

The pandemic led to lots of supply issues, but like so much else in the world, the roots of these issues stretched back years or decades:

-Over-building of single-family homes in the 2000s led to an Underbuilding of single-family homes form 2007-2021; a reasonable estimate is the United States needs 2-4 million single-family homes, disproportinately in the modestly priced starter homes. (More of any housing will help).

-“Just in Time” delivery squeezed a few more pennies in profits per share (not insubstantial) but the cost was a fragility that led to massive shortages in critical items, most especially healthcare.2

-Labor Shortages trace back to the post-9/11 era, when the Bush Administration changed the rules of who can stay in the United States after getting a college degree. That was followed by decreased legal immigration, an uptick in disability, COVID-19 deaths, and early retirement. A reasonable estimate is the United States needs 2-4 million more workers to staff our labor force and reduce wage pressures fully.

The delay in restarting the manufacture of semiconductors worked to push up prices in new and used cars; that was a significant element in the initial round of price increases.

Last, I have to mention Greedflation.3 I was skeptical when the term first came into use, naively believing that companies only raised prices when forced to, lest they lose the long-term goodwill of customers.

My views have since evolved.

The term is defined as companies taking advantage of the general mayhem surrounding an inflation surge to raise prices far more than their input costs have gone up. It is not price gouging per se, but a more general “Hey, everybody else is raising prices, why not us too?” If company management is there to (arguably) maximize profits, well then, price over volume is what many companies did to great effect.

Profits raced to all-time highs, helping to propel the stock market to ATH, as it climbed the wall of worry and chronic perma-bears and disbelievers.

~~~

Into this complex mess, a once-in-century pandemic comes along.

A few weeks before this occurred, in DC, Congress got itself tied into knots over renaming a few schools /libraries (this did not happen). Then the NBA shut down live games, and a cascade of closures followed throughout the broader economy.

The country along with most of the world shuts down.

Fear levels spiked. The inability to pass even the most basic of legislation was overcome by panic, and Congress passed the largest fiscal stimulus as a percentage of GDP since World War Two in the CARE Act (I).

Most observers were sanguine, but full credit to Wharton Professor of Finance Jeremy Siegel. He presciently observed that a fiscal stimulus that enormous would lead to a huge, albeit transitory surge in inflation.

And he was right.

With people WFH and the service economy partly, temporarily closed, consumers shifted to goods consumption. Our 60/40 economy became a 40/60 one. Give people stuck at home large stimulus checks, and the result will be a massive demand for goods that sends prices screaming higher every time.4

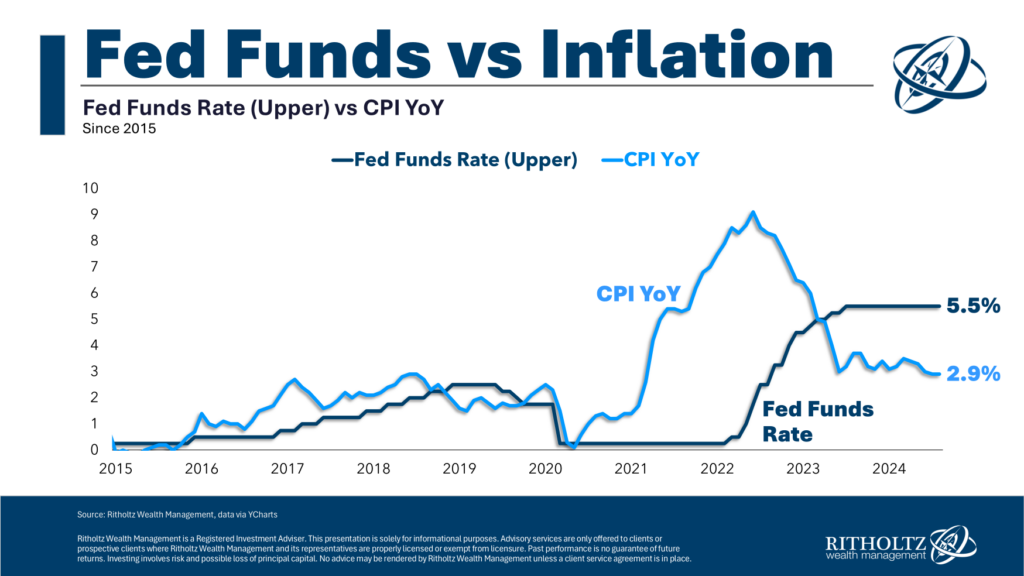

Inflation passed through the Federal Reserve’s 2% target in March of 2021; by December ‘21, CPI was over 7%. It would peak in June of 2022 at 9%. It came back down almost as quickly as it went up.

By June of 2023, it was obvious to any observer who understood how the BLS models worked that inflation had been defeated. CPI fell to about 3%, but that measure was somewhat elevated, as it included lots of lagged data about housing and rentals.

The Fed is large stolid institution, conservative in nature. They move slowly. Their incentive structure is asymmetrical: They are much more concerned with “Not Being Wrong” than they are in “Being Right.”

That complexity is not quite as contradictory as it may sound.

Consider the possibility of rate cuts in June 2023 (as I was advocating for at the time). Had they cut too soon, and inflation reignited, they look foolish. If it was not too soon, all they would have accomplished was: Providing credit relief for the entire bottom 50% of consumers; making more housing supply available; stimulating CapEx spending; encouraging more hiring; keeping the economic expansion going.

But here is the thing: They would have gotten precisely zero credit for that outcome. It was a modest risk with no upside to them.

So instead, they played it safe. They waited until it was beyond obvious that inflation was dormant and the economy was cooling.

We can debate whether the FOMC should have begun easing rates June 2023 (perhaps a smidgen early) or September 2025 (manifestly late).

Regardless, rate cuts are coming. They are likely fully baked into stock prices, which suggests another concern of Jerome Powell – not allowing the AI frenzy to turn into a full-on bubble. That is a conversation for another day.

Lower cost of capital, more homes available for sale, and a decreased cost of credit — assuming this all occurs without another increase in inflation — add up to a continued economic expansion, and perhaps modestly higher stock prices.

~~~

Enjoy the rest of your summer!

Previously:

Why the FED Should Be Already Cutting (May 2, 2024)

CPI Increase is Based on Bad Shelter Data (January 11, 2024)

Revisiting Greedflation (November 16, 2023)

The Post Lock-Down Economy (November 9, 2023)

The Fed is Finished* (November 1, 2023)

Inflation Comes Down Despite the Fed (January 12, 2023)

Why Aren’t There Enough Workers? (December 9, 2022)

Why Is the Fed Always Late to the Party? (October 7, 2022)

Who Is to Blame for Inflation, 1-15 (June 28, 2022)

How Everybody Miscalculated Housing Demand (July 29, 2021)

_________

1. At the time, I blamed the lack of robust fiscal action on “partisan sabotage,“ but that was widely pooh-poohed from both the Left and Right. CARES Acts 1 & 2 (under Trump) and 3 (Under Biden) have only served to confirm that prior observation that we know what the proper playbook looks like; when we do not put that into effect, it is typically for all the wrong ideological and political reasons.

2. This is a national security issue, and I support the Federal Government mandating a 90-180-day supply of those critical to the nation’s health and well-being. If all companies MUST have a 3-month supply of widgets, then it should not affect the stock prices other than who compiles a supply most efficiently. And big penalties for stockpiling cheap overseas-made garbage that won’t work when needed.

3. And its cousin Shrinkflation.

4. By the end of 2021, vaccines had become widely available and the beginning of the end of the pandemic was in sight. What came next was the summer of revenge travel, more services spending, and a slow return to if not normal, then close.